Where next? Use of AI video in Pakistan election concerns experts

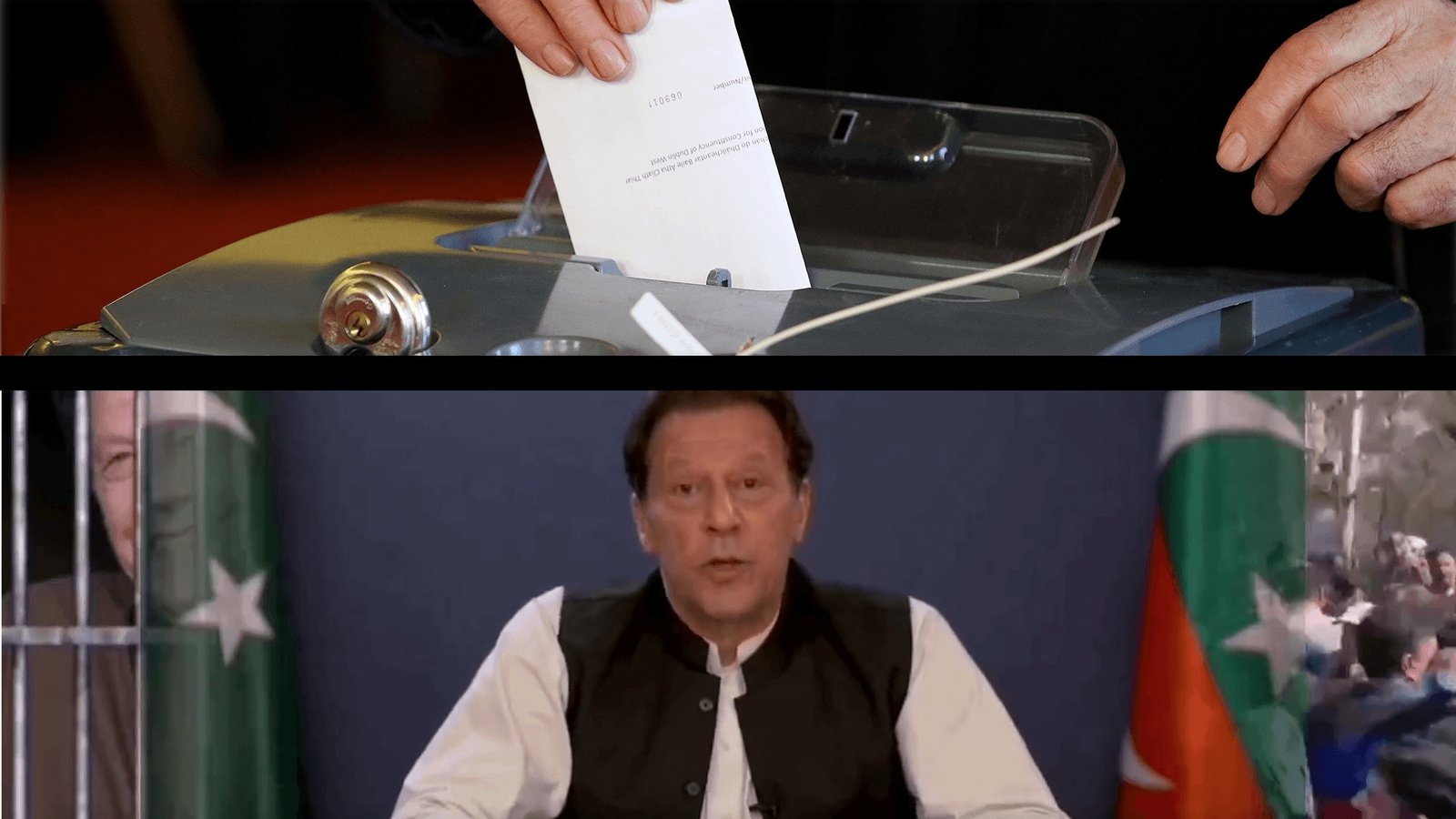

In a video posted to his official X account on Friday, former Pakistan prime minister Imran Khan claimed a landslide victory for his Pakistan Tehreek-e-Insaf (PTI) party in Thursday’s general election.

It was an election he had been banned from entering, as he is currently serving a 14-year prison sentence for corruption.

Candidates backed by his PTI party had won the most seats, he said. But the voice heard in the video was not Mr Khan’s own, it was a duplicate version of his voice generated using artificial intelligence (AI).

In the run up to the election, Mr Khan’s team posted several similar videos made using AI. Labelled as videos ‘authorised’ by Mr Khan, they contained audio that sounded like him, and video that looked like him, both of which had been artificially generated.

While clearly labelled as AI-generated, the deployment of the technology used to make such videos – sometimes referred to as ‘deep fakes’ – during an election has worried experts focused on public trust and democracy.

Chairman Imran Khan’s victory speech (AI version) after an unprecedented fightback from the nation that resulted in PTI’s landslide victory in General Elections 2024. pic.twitter.com/Z6GiLwCVCR

— Imran Khan (@ImranKhanPTI) February 9, 2024

Some are concerned such technology will be misused consistently in forthcoming elections. In 2024, Irish people will be asked to vote in two referendums in March, and the European parliament elections in June, while some political commentators also predict a general election may be called.

Globally, around half of the world’s adult population will be asked to vote in 2024.

Mr Khan came up with a “highly creative solution” for campaigning from behind bars, according to Jessica Cecil, a former journalist who focuses on disinformation and its impact on democracy.

However, it created “a situation where you don’t know whether those were Imran Khan’s words or they were the words of the press office for Imran Khan,” she told Prime Time.

Ms Cecil is a former senior BBC executive, and founder of Trusted News Initiative. It was set up to bring news organisations and technology companies together to combat disinformation.

“The use of clearly-labeled AI within political campaigns – and we’ve seen it in Brazil, we’ve seen it in Pakistan – creates a situation and an environment which is really difficult to navigate,” Ms Cecil said.

“Because it creates an environment in which voters potentially find it hard to distinguish what is real and what isn’t, even if it has been clearly labeled.”

Professor of Politics and Public Policy at Queen’s University Belfast, Muiris MacCarthaigh, says the speed at which AI technology is developing is “extraordinary.” He believes that could present challenges to the democratic process, especially if content is not clearly branded as being AI-generated.

“It’s a very risky thing for a candidate or a political party to go and engage with the more advanced forms of AI… like deep fakes and fake audio clips and so on. I mean, it might work to your advantage, but the risks are enormous.”

Prof MacCarthaigh has previously published research looking at how AI could affect the electoral process.

Other more malicious uses of AI were also evident in the run-up to the Pakistani election. In one instance, audio and video was made using AI and circulated online showing Mr Khan calling for a boycott of the election.

Another showed PTI candidate and former minister, Muhammad Basharat Raja, supporting Mr Khan’s supposed calls for a boycott.

Mr Raja later posted a video clarifying the situation and saying that he was still running as a candidate.

“There are bad actors out there attempting to manipulate this for profit for their own ends. And you have foreign states that are very actively involved in this area as well,” Ms Cecil told Prime Time.

In recent months, other examples of AI-generated audio have also been deployed during votes in the United States and Europe.

In late January, a ‘robocall’ system was put into use in the run-up to the New Hampshire Democratic Party primaries, in which a voice claiming to be US President Joe Biden told voters not to cast a ballot.

The use of AI-generated robocalls has since been banned in the US, and the New Hampshire Attorney General has launched an investigation.

Prior to the election in Slovakia on 30 September, an audio recording purporting to be the leader of the Progressive Slovakia party, Michal Šimečka, was circulated on social media and messaging apps.

It purported to be Mr Šimečka speaking with a journalist about how to rig the election, partly by buying votes.

Verification specialists at the news agency AFP said the recording showed numerous signs of manipulation or creation with AI.

“I think what we’re seeing at the moment is an experimental phase in the use of AI, [but it] looks set to increase,” Ms Cecil told Prime Time.

“We’ve got enough pointers at the moment to what is quite a concerning environment,” she added, warning the very existence of the technology itself, which is almost wholly unregulated and unmonitored, could be problematic.

“[It] sends a signal to voters that you don’t know what you can trust. Potentially, that will create a situation where you don’t know how much you can rely on the outcomes of elections, even if fake media itself has played a relatively small part.”

Prof MacCarthaigh says the potential prevalence of AI-generated misinformation could distract from the democratic process.

“The filling of the political debate by false information and the attempts to address it, it is problematic. I mean, there’s no doubt about it. Political parties and individual candidates engage with this at their peril.”

“It’s less so that it can taint candidates and so on, but it can consume a lot of the narrative, it can consume a lot of the debate when people have to deny things and so on and say, ‘no, this isn’t true, this is a deep fake, or this is false information.’”

“The danger is that democracy relies on individuals knowing that what they see is legitimate, and making decisions on the basis of that,” Ms Cecil added.

“And if you don’t know what you’re seeing is legitimate, then how can you make decisions on the basis of that?”

She says regulators, State organisations, social media companies and the general public are “running to catch up” with the pace of improvement in the technology, which has seen AI-generated videos go from looking like poor-quality animation to photorealistic video within the last 12 months.

Prof MacCarthaigh says the concern is that AI-generated disinformation could push democracy in a direction that is not benefiting society.

“How democracy is fortified or strengthened or made more resilient to this is a challenge that nobody has really successfully dealt with yet,” he said, “which is why this is an urgent task to deal with any threats that are out there.”