Trimble and Adams ‘edging towards mutual respect’

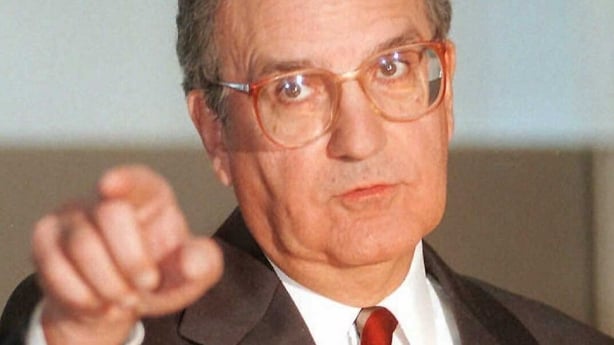

Newly released government documents reveal surprising insights into one of the key relationships in the peace process – that between Ulster Unionist Party leader David Trimble and Sinn Féin leader Gerry Adams.

Despite his visceral distaste for republicanism and anything to do with the IRA, Trimble appeared fascinated by Adams.

Two months before the Good Friday Agreement, Trimble’s deputy, John Taylor, said that Trimble wanted to meet Adams, to try to persuade him to “acknowledge in one form or another the principle of consent”.

After Good Friday, senior British official Quentin Thomas told his Irish counterparts of “the importance of the personal chemistry between Trimble and Adams. He believed that they are edging gradually towards mutual respect”.

As evidence for this, Thomas claimed that “Trimble now accepts that Adams is personally deeply committed to making the agreement work (whatever about some of his colleagues in Sinn Féin)”, while Adams had told somebody that “Trimble is playing a blinder”.

As the impasse over IRA decommissioning continued to stall the establishment of the Northern Executive, the two men had a private meeting in September 1998 to try to reach an agreement – but they came away with very different impressions of what was said.

According to Sinn Féin, Adams “told Trimble straight out that there was no point in jumping up and down on decommissioning. This would not deliver the IRA, and other ways forward had to be found”.

But Trimble told Irish diplomat David Donoghue that he had been encouraged by “the Sinn Féin leader’s apparent agreement” with his own views. Trimble “concluded from their discussion, and from Adams’ generally positive and receptive body language, that the Republican movement will ‘do something’ on decommissioning within the next couple of months”.

Donoghue, however, had his doubts, noting that Trimble “seemed to be relying heavily on an absence of loud protest from Adams at the scenario described”.

Early the following year, Trimble told his close ally, the historian Paul Bew, that he had concluded from his contacts with Adams that IRA decommissioning would happen in the short term, and that he expected “everything to be alright eventually”.

Bew wasn’t convinced, and nor was Donoghue, who reported to Dublin: “It seems likely that Trimble, who is perhaps not used to Adams’ subtlety of argument and presentation, is seriously misreading Sinn Féin’s position”.

This misreading may explain the depth of Trimble’s reaction when IRA decommissioning did not in fact happen in the short term.

He and Adams continued to meet in private, but an encounter between delegations from the two parties, chaired by Senator George Mitchell in September 1999, saw a heated argument between them. Mitchell was taken aback by “the ferocity of the exchanges” in what was “a very difficult, emotional meeting, with much mutual recrimination”.

Adams asked Trimble directly what he wanted, to which Trimble replied: “I want a complete and unequivocal ceasefire, I want total disarmament and I want it started now”.

Adams said if he were able to, he would bring in a bunch of rifles now – it would make his life much easier. But, he added, “it was simply not reality”.

At one point, according to Mitchell, Trimble “turned deep red” with anger. Adams told him directly: “You are the best bet we have. We want to work with you.” Trimble replied that “certain things” (meaning decommissioning) would have to happen first.

In an indication of the gulf between the parties, Trimble ended the meeting with a long quotation from Oliver Cromwell; Martin McGuinness replied: “Cromwell is not the man to be quoting at us!”

Mitchell reported to the Governments that the gap between the sides remained “enormous”, and that Adams and McGuinness privately thought Trimble could not deliver. But Mitchell still thought “the ball remains in play and that both sides are serious about giving it one more real go”.

In March 2001, with the process deadlocked again, Taoiseach Bertie Ahern suggested it might be a good idea if Sinn Féin and the Ulster Unionist Party were to meet regularly in an effort to defuse problems.

Perhaps surprisingly, the idea was taken up, and a small group consisting of Martin McGuinness and Gerry Kelly of Sinn Féin, and the UUP’s Reg Empey and Michael McGimpsey, met in private most Thursdays.

Empey told Irish official Dermot Gallagher that he liked and worked well with McGuinness, but that he despaired of what he saw as Sinn Féin brinkmanship. “He had pleaded in vain with Martin McGuinness on a number of occasions to try and resolve outstanding issues when things were quiet and calm, rather than waiting until the parties were up against a deadline, and a crisis had, inevitably, developed”.

Having reported the existence of the group to a small number of colleagues, Gallagher was taken aback to see his memo circulated more widely than he anticipated. He followed up with a plea for discretion: “It would be unfortunate and very unhelpful indeed if there was any reference whatsoever to it by colleagues”.

By David McCullagh and Shane McElhatton

[Based on documents in 22022/45/3; 022/45/424; 2022/45/426; 2022/45/432; 2022/45/435, 2023/155/6; 2023/155/25; 2023 155/23]