The long road to the Stardust inquests

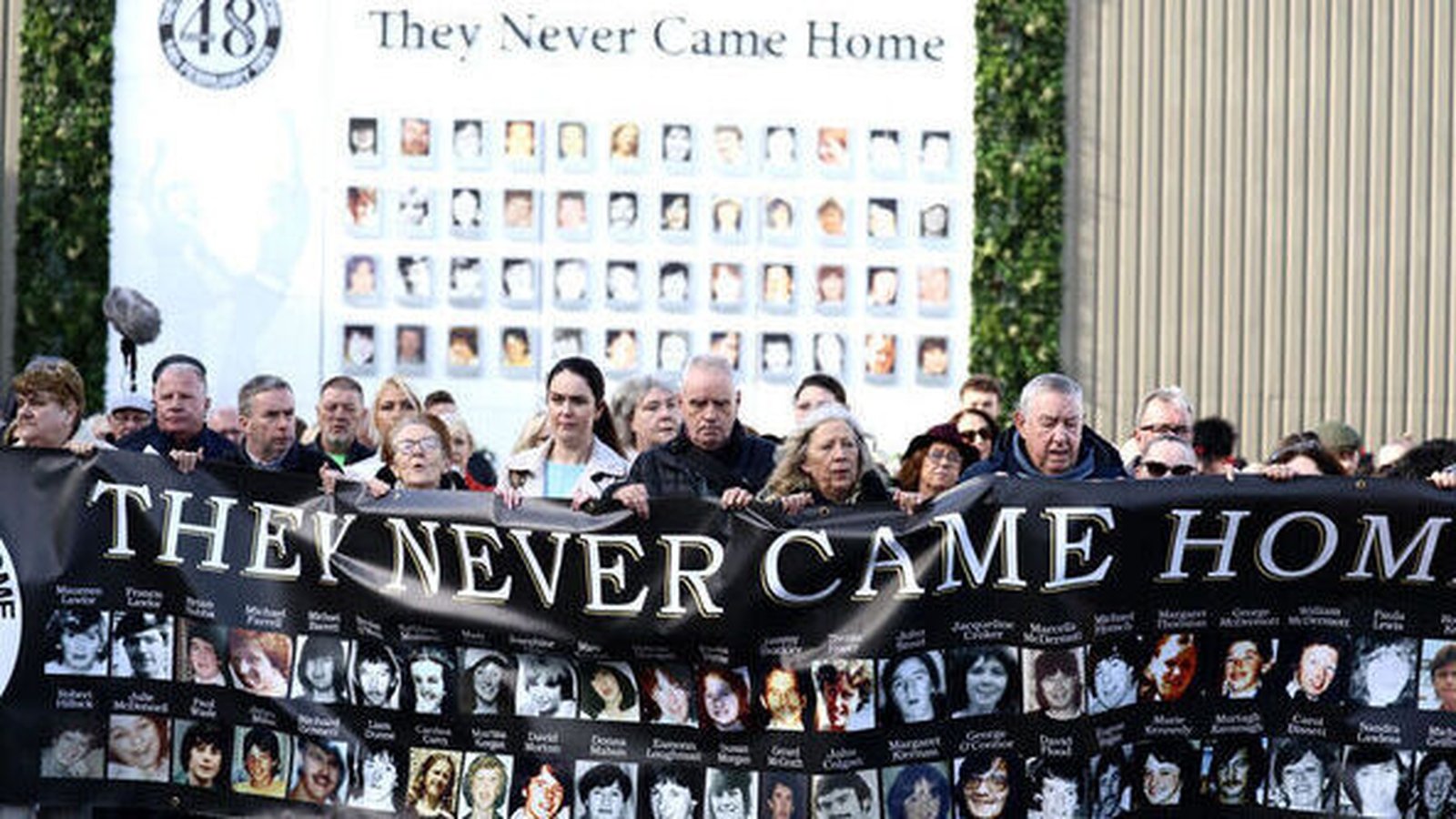

The longest-running inquests in the history of the State have ended with verdicts of unlawful killing in the case of all 48 victims.

As lengthy as it was, the campaign to get them established has been longer.

Relatives of the dead have been campaigning for years, for a lifetime.

Ever since the early hours of Saturday 14 February 1981, they have wanted to know how and why their loved ones died. Why, after going out for the night, they never came home?

For those involved, especially the relatives, the inquiry has been exhaustive and exhausting.

All aspects of the disaster were dealt with, the background to how the Stardust complex came to be, the circumstances of its conversion from an old factory, how the club was run, the policies in the place, the immediate run-up to the fire, its outbreak and its devastating consequences.

As the inquests have now come to an end, it is clear that this was a thorough and comprehensive questioning of how and why those 48 never came home.

Dublin, 1981

On day one of the inquests, coroner Dr Myra Cullinane said the 48 victims who died in the fire would be central to the proceedings and so that proved to be.

Their faces, captured in photographs and prominently positioned in the courtroom, looked across these hearings for the duration.

The photos and the faces were a reminder of why these inquests were taking place.

Their hairstyles and fashion on show in those images also pointed to a different era, a bygone age of teenage perms and thin moustaches.

They also illustrated the 43 years that had passed and the sheer length of time that has elapsed to get to the point of these fresh inquests.

From the testimony given over the twelve months, it was clear that the Dublin in which the Stardust fire occurred, the Dublin of 1981, is very different to the Dublin of today.

The fashion and the music referenced – such as Blondie, Boney M, Donna Summer, Rainbow – spoke too of that time.

It was a bleak capital city where, for many, money was tight.

Many families recalled how their teens had left school early to get a job to contribute to the household. It was a time when not all families had cars or landlines.

It is also clear that this was a disaster very much on Dublin’s northside.

The Stardust was in Artane and most who died were from the local area.

The addresses of 36 of the victims were from the Dublin 5 postcode – Artane, Coolock, Raheny.

The workplaces mentioned, Cadbury’s and the Northside Shopping Centre, also pointed to the geography of where the disaster took place.

However, to say that it just affected the capital’s northside would be inaccurate.

Susan Morgan, 19, was from Derry. She went to the Stardust that night along with her friends, described in court as one of the original ‘Derry Girls’.

She died in the fire along with her boyfriend, Paul Wade.

Robert Hillick and James Millar were from Belfast and had moved down south to work on the building sites and to get away from the Troubles. Both friends perished.

Kathleen Muldoon, who was in Dublin to pursue a career in nursing, was originally from Kells, Co Meath.

Where the disaster happened though is significant, as the families will tell you that if it had happened south of the River Liffey, they believe it would have been handled differently and not have dragged on as long as it did.

The road to the inquest

As these inquests finally got under way in April last year, there were two questions commonly asked by those who were not overly familiar with this case.

Why are these inquests being held now and what will they achieve?

The answer to the first question is both simple and complex.

The short answer is that the inquests were held because in 2019 the then attorney general Séamus Woulfe directed they should.

The more thorough answer is that the AG’s direction followed a sustained campaign by the relatives.

For years, they fought.

A central and more recent figure in it too was the solicitor, Darragh Mackin.

His instrumental role in the campaign was referenced in court as the proceedings neared their end.

Original inquests were held over a five-day period in 1982 but were widely regarded as insufficient as only the medical causes of death were recorded with no reference to the surrounding circumstances, in particular, to the cause of the fire.

“I therefore consider that in the original inquests there was an insufficiency of inquiry as to how the deaths occurred,” Séamus Woulfe wrote.

“The scale and the horror of the tragedy was such that was that it was and remains the greatest such disaster to have occurred in the history of the State … I am satisfied that fresh inquests should be held,” he said.

There have been other inquiries too of course, mainly the 1982 Keane Tribunal.

It began its hearings two months after the fire, sitting for 122 days.

Many of the issues discussed in the fresh inquests were first aired at Keane 43 years ago and in many ways, it is a heavyweight document and makes some damning findings about how the nightclub was being run and the people running it.

For the families though, Keane is flawed because of its conclusions around the cause of the fire.

The evidence: What caused the Stardust tragedy?

It found: “The fire was probably caused deliberately, the most likely mechanism being the slashing of some of the seats with a knife and the application of a lighted match or cigarette lighter to the exposed foam, or the ignition of newspapers on or under the seats.”

That finding, that the fire was “probably caused deliberately” has haunted the families ever since.

They felt it impugned those who lost their lives. The survivors from the night also felt the same way.

That controversial Keane finding had another effect too. It allowed the Butterlys, who owned and ran the club, to make a successful compensation claim against Dublin Corporation and they were awarded IR£580,000.

In 2009, Keane’s conclusion on the cause of the fire was expunged from the record by an act of the Dáil.

Nevertheless, it still lingered.

For the families, the fact that it was gone was not good enough, it needed to be replaced.

In directing for these fresh inquests to take place, the AG also said there was an “entitlement of the families of the victims to the public revelations of the facts”.

For the relatives, this was an important part of these inquests.

A generation, if not two, has passed since the 1981 fire, so for the younger audience it was probably the first time they had ever heard of the disaster.

Such was the size on the proceedings, the Dublin District Coroner’s Court moved to the more spacious surrounding of the Pillar Room, on the grounds of the Rotunda Hospital.

The hearings were held in public with the media present, which meant the accounts of what happened were well aired.

The families wanted the Stardust back in the spotlight and the public to know about their loved ones who lost their lives in such an appalling way.

The 48 dead

Ever since the deadly blaze, relatives have said the victims were regarded merely as numbers.

As well as tackling the fundamental issues of the cause of the fire and the condition of the exit door, for the relatives, these inquests were also about giving the 48 their identities back.

This was achieved through the “pen portrait” module of the inquests, when family members spoke of the lives lost.

The jury was told about the dead’s hobbies, their ambitions, and plans for the future.

They were not, officially, part of the evidential phase of these hearings, but there’s little doubt it made an impact on those listening.

Each of the victims’ stories are worth telling and have been on these pages since the inquests began and while there is no hierarchy of grief in a case like this where each of those died had their lives cut short, the tragedy of it all can be captured in just a few snapshots.

The inquests heard George O’Connor was quiet and reserved.

He had never been to a dance before, the Stardust was his first and last.

Martina Keegan had brought a Valentine’s Day card with her for her boyfriend David Morton.

It was found in water outside the following morning.

Richard Bennett did not have a tie on and was initially refused entry to the nightclub.

“One of the lads” was handing ties back out the door, Richard got one and that got him through.

Brian Hobbs’ parents had actually been in the Stardust complex earlier in the night.

As they left, they smelt and saw smoke. They did not know their son was inside.

Teresa McDonnell’s last words to her sister were warning her of the fire.

“Lorraine. Get out, there’s a fire.”

They are just five quick summaries illustrating the heartbreak of the disaster, there are another 43 stories, equally sad and equally worth listening to.

The pen portrait testimony was often harrowing and emotional. The stories the families told were unique but there were common themes running throughout.

The families spoke of the initial shock of the night, the desperate search for their loved ones, and the confusion over identifying the dead.

Then, for the families, came the aftermath.

They spoke of the devastation for those left behind, the survivor’s guilt.

There was anger in them too as they told of their decades-long search for answers.

Many families were ripped apart, siblings separated as parents struggled to cope with grief.

There were tales too how survivors and relatives turned to alcohol or moved away out of the country.

There was also the story of the McDonnells. Julie McDonnell was 20 when she died in the fire.

Her sister, Lorraine, also attended that night, but survived. In the years afterwards, her mental health worsened.

The court heard how Lorraine took her own life the night before she was due to collect a compensation cheque.

It is clear that the Stardust disaster claimed many more victims than the 48 who perished in its fire.

There was another grim testimony too towards the end of these inquests and it heard from three expert pathologists who gave evidence on the causes of death, the victims’ last known movements and how their remains were identified.

That evidence painted a particularly bleak picture of how the families, desperate to hear word of their missing loved ones, drove around the empty streets to the city’s hospitals hoping, praying that their son or daughter, brother or sister had survived.

Those despairing journeys would eventually lead to the Dublin City Morgue, which the inquests heard, was overrun with bodies.

The inquests heard, such was the state many of the victims were in, they were identified through their jewellery, their clothing, their dental records and in the case of five of the victims – Richard Bennett, Michael French, Murty Kavanagh, Eamonn Loughmann, and Paul Wade – through DNA testing conducted in 2007.

Many of the relatives of those men died before the identifications, not knowing if the grave they had been visiting was in fact the right one.

The accounts of how family members identified their loved ones by their belongings was heartbreaking.

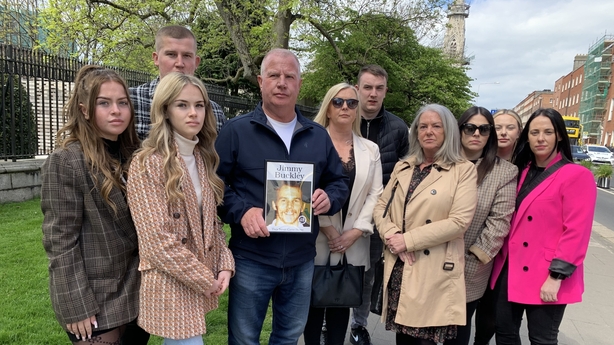

Jimmy Buckley’s remains were identified by his wife by his wedding ring. The couple had been in the club together that night.

Jacqueline Croker’s identity was confirmed by her fiancé by the engagement ring she had been wearing.

Josephine Glen, 16, was identified by her brother.

Margaret Kiernan’s remains were identified by her father, from an eternity ring she was wearing that belonged to her mother, which he had bought.

Donna Mahon was identified at the morgue by her sister from the bracelet she had given her and was wearing on the night.

The court heard how 17-year-old Caroline McHugh was identified by her jewellery and some of her clothing, a tiny portion of maroon-coloured cloth.

That was particularly poignant, the jury heard, because Caroline’s mother, Phyllis, had left the clothes out for the disco before she travelled to England for a family wedding.

Caroline was their only child.

Read more: Profiles of all 48 victims of the fire

The survivors

There was distressing evidence also from the survivors of the night, as they broke down recalling the horrors of the nights.

There were over 800 patrons inside the Stardust club when it was engulfed by flames. The majority of those made it out safely.

More than 100 were physically injured but the inquests heard many more than that suffered.

They were the “lucky ones” who made it out, but when it comes to this disaster, that term is relative as survivors detailed how they still feeling the effects 43 years on.

Liam Hennessy was 31 years old in 1981. In court, he looked all of his 70-plus years.

He made his way to the witness box with the aid of a walker, his story of the night moved some of those in the courtroom to tears.

In a low voice, he spoke into the microphone and told of his repeated but ultimately unsuccessful attempts to bring a family friend to safety.

David Flood was 18 years old and had fallen asleep in a seat in the north alcove of the club.

“There was nothing I could do”

As people were alerted to the fire, Liam Hennessy tried to wake David up. He shook him good, he pulled at his legs.

Liam Hennessy spoke of the stampede, the fire ball and the smoke that were all swirling around as he tried to rouse David.

The jury heard how Liam Hennessy returned to David a second time and shook him again but at that stage the black fumes meant he could not see anything.

“Then I let him go,” Liam said. “There was nothing I could do.”

Benny Murphy gave evidence of how after he made his escape, he looked in Exit 4 from the outside and saw a girl burning.

He told gardaí in 1981 that no one could do anything for her as the exit was on fire.

At the end of his testimony, he said that every day he wakes up and has memories of the girl.

“I don’t know if she’s still alive. Her clothes were burnt off. Her stomach was breathing up and down. It was a horrible, horrible thing,” he said.

“I have to face every day for 42 years…looking back through Exit 4 and seeing this girl burning and she was close and you can’t get her.”

“For the people who survived,” he said, “there should be some sort of counselling or something.”

The survivors too spoke of the screams coming from those trapped inside, they were shouting for the lives.

Joseph Cumiskey described how he tried to break the windows outside on the front of the building with a hammer in an effort to get people out but could not do so because of the bars across them.

Through tearful testimony, he said: “There was nothing I could have done.”

The inquests also heard how steel plates were welded to the inside of the toilet windows in the weeks before the fire.

Another witness, Paula Toner, who was 17 at the time, also described the scenes on the outside.

She said people were standing at the toilet windows and shouting to the people inside to “put their heads down the toilets”.

Those who escaped also spoke of the chaos inside as the fire quickly took hold.

They told of “fireballs” and a “mushroom of fire” as the blaze spread from something that looked like it was containable to something uncontrollable within a very short period.

They spoke about the panic, how it was “every man for himself” as hundreds scrambled for the doors. They got no direction from staff.

What followed was a “stampede” as people spoke of the crush in the foyer, waiting to escape as the lights went out and as the flames and dark smoke grew ominously closer.

What is worth remembering too is that many of the people inside were children.

The event on the night was meant to be for over 21s, but many were underage and 38 of the 48 who died were under 21.

Thirteen of the victims were under 18, while nineteen of them were aged 18 or 19.

Given the incomprehensible loss of life that night, the heartbroken families understandably wanted the Stardust back in the spotlight – and the public to know about their loved ones who lost their lives in such an appalling way.

In the end, these inquests concluded as they had started – with the gathering of families outside the gates of the court.

One year ago, they came here looking for justice.

After 122 days of hearings and testimony from over 370 witnesses, and days of jury deliberations, the relatives got what they were hoping for.

They also got more than that – they got the verdicts they’d been seeking for the last 43 years.

They got the Stardust back in the spotlight, and the victims’ identities and dignity vindicated.

Justice for the 48.