Legacy issues still seem too tough a nut to crack in NI

On the night he was abducted and murdered, 61-year-old Sean Brown was doing something people up and down the country do every evening of the week.

The chairman of Bellaghy Wolfe Tones GAA in south Derry was locking up the gates of his club when he was assaulted, abducted and murdered by a loyalist gang.

Tomorrow, RTE airs a documentary about the 1997 killing.

It had been one of the most high-profile of Troubles era inquests hurtling down the tracks towards the buffers of a British government-imposed 1 May legacy deadline.

The family counts Tánaiste Micheál Martin and GAA president Jarlath Burns amongst its supporters.

The case is compelling.

Titbits of intelligence emerged during the inquest, but the bulk of it was withheld on the grounds of national security after legal applications by the police, military and security service.

What we do know now is shocking enough.

Some 25 people, including state agents, were linked by intelligence to Mr Brown’s murder.

Surveillance on a key suspect was suspended the night before the murder and reinstated the following day.

We can only speculate about what else might be in the intelligence files because when they were produced to the Browns’ solicitor they were completely blacked out.

In one file there were 52 pages. Every word was redacted.

“This is the legal mechanism by which the state keeps its secrets,” solicitor Niall Murphy tells the documentary, leafing through the blanked-out pages in a large ring binder.

The looming May deadline means there is a rush to get legacy matters concluded.

If they are not, they fall into a new information recovery body in which few have faith.

No one is letting go until the past is properly and comprehensively dealt with, painful as that may be.

The courts are busy with cases. The public prosecution service is issuing decisions on files that have been in the works for years.

Almost without exception the decision is for no prosecutions.

Issues of the availability and admissibility of evidence are recurrent themes – unsurprising when the cases date back decades.

But no one should be under any illusion that this last-minute wash-up is going to wipe the legacy slate for society.

When journalists cover these cases now they are speaking, not to spouses and siblings of victims, but to their children and grandchildren.

No one is letting go until the past is properly and comprehensively dealt with, painful as that may be.

The recent findings of the Kingsmill massacre inquest are a case in point.

It set out in forensic detail how IRA gunmen flagged down a van of factory workers in south Armagh almost 50 years ago, separated the only Catholic from his Protestant colleagues and sprayed them with automatic gunfire on the side of a narrow rural road, leaving ten men dead.

The only survivor, Alan Black, now in his 80s, said his friends were calling from the grave for justice and the pursuit of it would continue.

It was several days later before the media got the opportunity to ask Stormont First Minister Michelle O’Neill about the inquest findings.

The IRA had never acknowledged its role in the murders and republicans had not engaged with the inquest.

Sinn Féin’s northern leader was asked whether she wanted to apologise on behalf of the republican movement for Kingsmill – an atrocity that happened before she was born.

It is tricky territory for republicans, not wanting to condemn the IRA but not wanting to be seen as ambiguous on such an overtly sectarian attack.

Her job, she said, was to build towards the future and heal the wounds of the past.

“I am sorry for every lost life, including those in the Kingsmill disaster,” she added.

Some unionists picked up on the use of the word “disaster”.

They pointed out that far from being an accident, it had been a pre-planned and ruthlessly executed massacre.

It was an example of how the past still resonates in present day politics.

If legacy matters are not all but concluded by 1 May 1, new British government legislation kicks in.

Opponents say at its heart is about protecting British army veterans who served in Northern Ireland.

It effectively shuts down new civil proceedings and bars fresh criminal cases.

Families already in the judicial system have accused the authorities of deliberately running down the clock towards the 1 May deadline to deny them justice.

Remaining Troubles inquests, which have not reached an advanced stage, will be transferred to a new body, the Independent Commission for Reconciliation and Information Recovery.

There are around 14 such inquests covering the deaths of almost 70 people.

The commission will also provide reports to families who approach it for information.

Former paramilitaries who co-operate to provide that information will get amnesty from prosecution.

Families already in the judicial system have accused the authorities of deliberately running down the clock towards the 1 May deadline to deny them justice.

Coroners, conscious of the impending deadline, have been critical of the police, military and security services for the time taken to furnish information.

The inquest of Mr Brown came to a sudden halt on 14 March.

Coroner Mr Justice Kinney said because inquests cannot sit in closed hearings there was no way for him to incorporate the intelligence material.

Without it, his duty to carry out a “full, fair and fearless” investigation into Mr Brown’s murder would be “seriously compromised”.

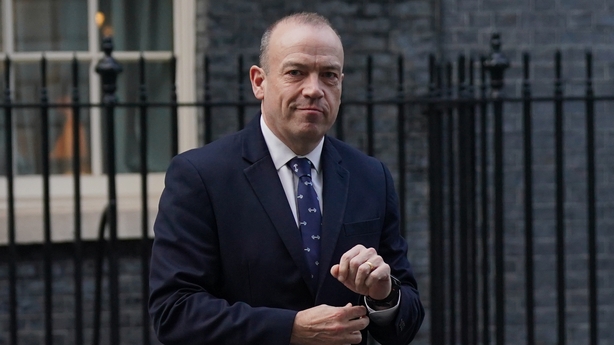

With regret he announced he was stopping the inquest and writing to Northern Secretary Chris Heaton-Harris requesting a public inquiry.

Such inquiries can hold closed sessions and could deal with the sensitive material.

The judge asked for a decision from Mr Heaton Harris within four weeks of receipt of his letter, keeping it within the 1 May deadline.

Last week, the Mr Heaton-Harris issued his response.

Instead of the decision on a public inquiry, the Northern Ireland Office announced it was legally challenging aspects of the conduct of the Brown inquest.

It appears the challenge is linked to the decision to give the family a very limited summary of the material in the intelligence files.

The British government seems to feel that flew in the face of a long-standing convention that UK authorities neither confirm nor deny the existence of state agents.

The Brown family believes the latest legal challenge has an alternative purpose.

It ties them up in a legal proceeding that will take them past the 1 May deadline, effectively ending any chance they will get the justice they are seeking.

It looks like a cynical move. One the Browns described as “an attack on the truth”.

Legacy was set to one side when the Northern Ireland peace process was being constructed.

It was just too tough a nut to crack. It seems little has changed over the years.

The Sean Brown documentary: Murder of a GAA Chairman airs on Monday 22 April on RTÉ One at 9.35pm and on the RTÉ Player.