Irish surgeon on operating in Gaza

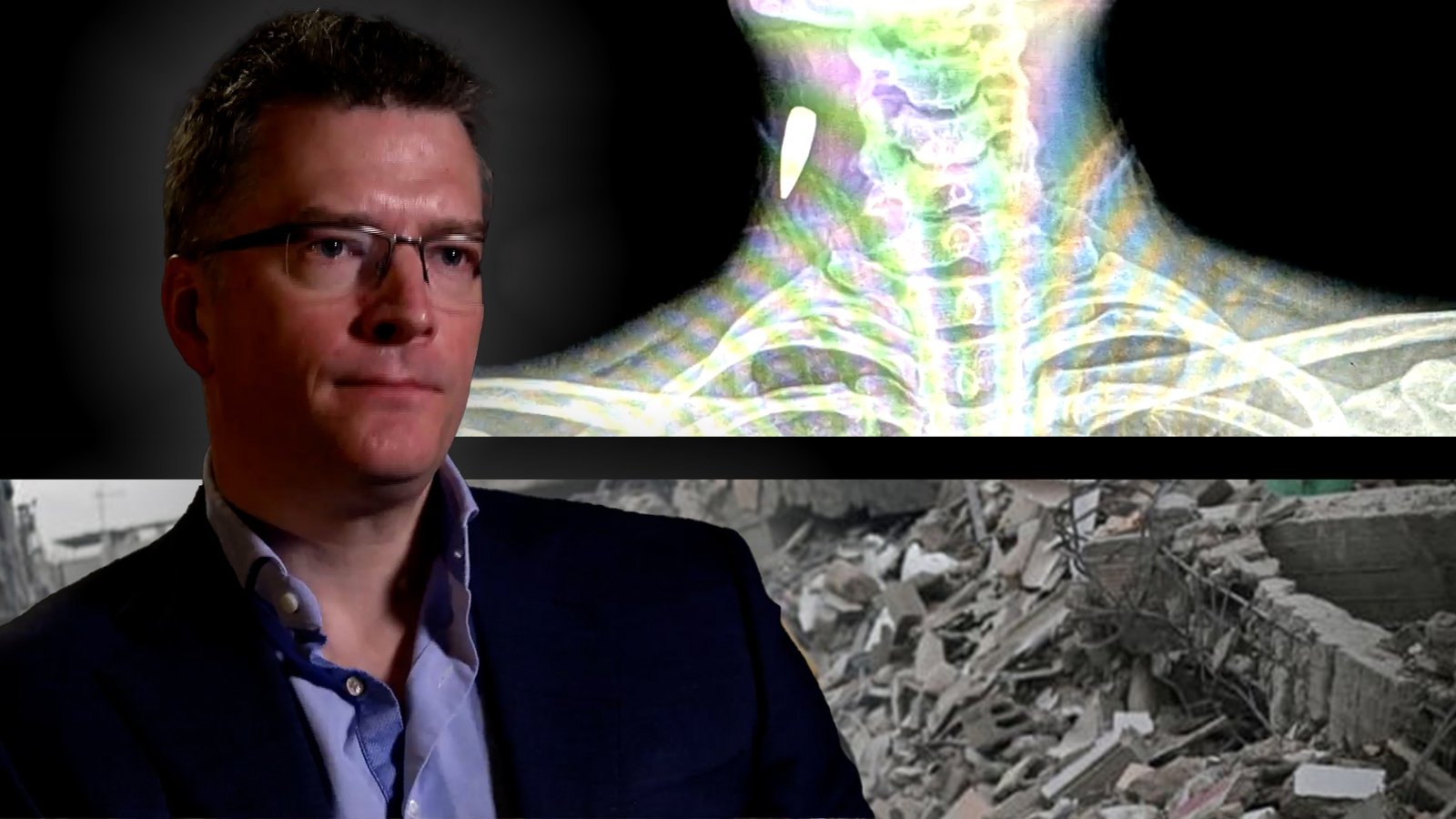

Vascular and trauma surgeon Dr Morgan McMonagle returned from Gaza two days ago, where he was treating injured Palestinians in a field hospital in between the southern cities of Rafah and Khan Yunis.

“Mostly we’re seeing gunshot wounds, blast injuries and shrapnel,” he told Prime Time.

“It’s actually worse than you can imagine, it’s worse than what you’ve seen on social media and whatever bits of media have come out on mainstream TV.”

Around 1.5 million Palestinians are sheltering in Rafah, which is now a vast refugee camp, populated by people who have fled from other areas in the Gaza Strip. The city is under constant Israeli bombardment.

The health ministry in Gaza, which is controlled by Hamas, said on Thursday that more than 30,000 people have been killed and more than 70,000 injured since 7 October.

Dr McMonagle, who is based at University Hospital Waterford, has spent time in war zones in the past, including in Ukraine, where he trained medics. He says his desire to work in such difficult environments comes “from a deep desire to want to use your skills in the best possible way.”

“I suppose you have to have a sense of injustice or recognising injustice in whatever environment you’re working in.”

“They [civilians in Gaza] have no way of defending themselves, they have no way of defending their property, their children, their family, and they’re basically just hoping for the best, hoping that they won’t be killed, hoping they won’t be injured, hoping they won’t be maimed.”

The journey

Getting into Gaza as a foreign surgeon involved a “huge amount of red tape involved at a security level,” Dr McMonagle said.

Doctors must be on a special NGO list that goes to the Israel Defense Forces, Israel’s intelligence service, the Egyptian government as well as the Palestinian Health Authority, Dr McMonagle said.

The journey itself is long and gruelling. Dr McMonagle flew into Cairo, drove across the Sinai Peninsula, before going through at least ten security checkpoints while crossing the Egyptian border.

“You were sitting there waiting to be processed, and then you sit in a bus…you probably length of three football fields, and then you cross into Rafah.”

On the road to Rafah, Dr McMonagle said he saw a “huge backlog of trucks that are clearly delivering aid.

“They’re all facing towards Gaza, they’re all facing towards Rafah. I would say in total, we had about 20 miles of trucks at various places along the way.”

The hospital

Dr McMonagle worked in a field hospital between Rafah and Khan Yunis set up in a “deconflicted zone” the size of “two football fields”.

“It was a field hospital set up specifically to deal with trauma, because of the huge amounts of trauma that they were seeing.”

The kind of wounds and trauma injuries Dr McMonagle was seeing were shocking. But despite working in a war zone in horrific circumstances, morale was high between staff.

“The team morale was fantastic. There was a fantastic esprit de corps amongst everybody, nurses, the doctors, everybody in the field hospital.”

Given the sheer number of people needing medical attention, the hours were long and the luxury of sleep was not guaranteed.

“It was work every day. It was up at six, having had very little sleep because the bombs going off all night and the drones, which sound a bit like an old-fashioned two-stroke engine, like a lawnmower over your head, all night. Drones go all night,” Dr McMonagle said.

Generally, sleep came in between bombs, unless there was a very loud explosion, he said.

“If the windows rattle, we’re told it’s at least a kilometre away. If the whole house shakes, it’s probably less than a kilometre. That’s kind of the rule of thumb that we went by.”

Trauma surgeries

A couple of surgeries stuck out for Dr McMonagle. In particular, he operated on one man who survived being shot in the back.

“He was shot almost definitely at a distance because the bullet went into his back and stopped in his neck, and because it was causing symptoms and causing irritation, he asked for it to be taken out, which we did.”

Dr McMonagle said the bullet was likely fired from a high calibre weapon and believes the fact it didn’t kill the man instantly indicates that it was fired from considerable distance.

“It’s a large bullet and the metal surrounding it, the casing surrounding the bullet was not destroyed. So, it didn’t ricochet because the metal and a bullet will shatter if it hits off bone,” he said.

Dr McMonagle removed the bullet from the man’s neck, where it was lodged.

“We took that out and he was very, very grateful and he got discharged home same day.”

“He’s the luckiest man in Gaza,” Dr McMonagle told Prime Time.

Another man he operated on was not so fortunate. He suffered a shrapnel injury to his liver and had massive bleeding.

“He got to us just about on time but as we put him onto the operating table, he’d entered cardiac arrest,” Dr McMonagle said.

“The quickest way to stop bleeding is to open the chest and cross tamp the aorta in the chest, which we did, opened his abdomen, got control of his liver, got control of everything, packed him off, and he was doing okay,” he said.

However, the man wasn’t well enough to remove from the operating room’s ventilator which needed to be used by someone else.

“We had a different ventilator, which is a very old fashioned one, one I hadn’t seen before, which we put him on. And it was difficult during the night. It wasn’t functioning properly,” he said. The man went into cardiac arrest overnight and died.

Dr McMonagle says the IDF has been resistant to bringing ventilators into Gaza.

“I’ve been told that parts could be used for other purposes. I’ve been told it could be used to make weapons. I don’t know what kind of weapons. I’m not an engineer, but that’s the concern that we’ve been told.

Wounds

Infection is a huge problem. Patients often can’t get to the hospital before injuries become infected and the nature of the injuries mean that dirt is being driven deep into the wound.

“Almost every wound would get infected from a blast or shrapnel. The shrapnel is dirty, these patients are already in a situation where there’s zero personal hygiene, they’re malnourished. Malnourishment is probably one of the biggest causes of wounds not healing,” Dr McMonagle said.

“If wounds don’t heal, it becomes a breeding ground for bacteria, because bacteria like dead tissue more than living tissue, and the wounds get infected.”

Dr McMonagle says the patients who came in were “malnourished and severely malnourished.”

“Even though people are dying from the war and from the blasts and from crush injuries from the building and from gunshot wounds, we are now in a situation where we’re seeing starvation in this day and age, manmade starvation.”

Consequences

The nature of the injuries means that many patients are left with life-altering conditions, many are losing limbs with no hope of getting a prosthesis. Dr McMonagle believes that even among those whose lives were saved at the field hospital, there will be long-term consequences.

“They can’t function, can’t work, can’t earn money, can’t do the normal things. So you’ve not just crippled the population now, but you’ve crippled it for the next generation to come as well.”

Dr McMonagle travelled several times to Ukraine on similar missions to provide surgery for trauma injuries. He says the big difference in what he’s seeing in Gaza is the number of civilians being brought to the hospital.

“The difference is Ukraine is one military versus another military, for want of a better word. The narrative is like a proper war, if there’s such a choice of word. Gaza is a big army against civilians.”

He says that a sense of purpose is what keeps him returning to war zones.

“I enjoy acute surgery, I enjoy trauma surgery, and it’s one of the few areas where you can see someone severely injured or severely unwell, and you can make a difference very quickly.”

Though the medical staff was made up nationalities from across the world, Dr McMonagle said that the Palestinian doctors and nurses who worked alongside him had a special recognition for Ireland. “They’re all very aware of Ireland having spoken out on the human rights issue and South Africa. They’re very grateful that Ireland is standing with the human rights.”

Dr McMonagle had planned to stay in Gaza for four weeks, but as the Israeli offensive in Rafah intensified, it was considered too dangerous for foreign medics to stay. His Palestinian colleagues remain and the work of the field hospital continues for now.

“If our field hospital goes and other NGOs don’t get in, then I think we’re basically going to sit back in the western world and watch. We’re going to watch Gaza die.

“I think history will judge us, just like history judges us in the second world war, just like history judges us after Rwanda and any conflict you can name.”

Watch the full report from reporter Conor Wilson and producer Bridog Ni Bhuachalla on Prime Time on 29 February at 9.35pm on RTÉ One.