Economy and safety still appeals to new Irish arrivals

As young people continue to leave Ireland in search of work opportunities abroad, many others are drawn here for similar reasons.

Brazilians, Indians and Romanians are coming to Ireland in the largest numbers, according to the 2022 Census results.

While the topic of immigration has rarely been out of the headlines this year and has led to some contentious debate, those who have chosen Ireland as their home remain focused on the positives.

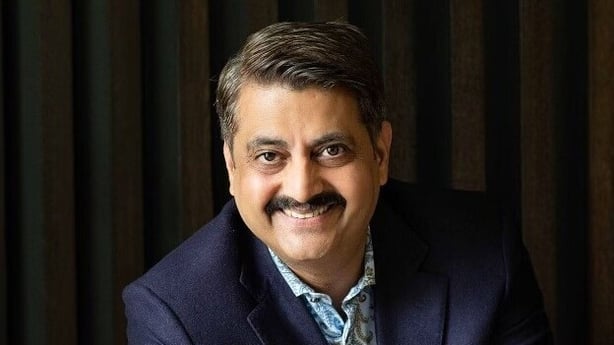

Sunil Ghai, a chef and restaurant owner in Co Dublin, said he believed it could only be a good thing to see more people coming to Ireland to take up work offers, and insisted that the conversation around immigration was important.

The 46-year-old, who has spent more than half his life in Ireland, said immigration was significant in creating more diversity, but was also of the view that people arriving have “to mix” into the Irish culture.

“You must learn about the culture,” he said. “You can’t say this is my boundary, and you must respect the different culture.”

The Indian community in Ireland has grown steadily over the last few years. In fact, it was the largest group of non-Irish citizens who moved here in 2021, with almost 10,000 arrivals.

Reflecting on his introduction to Ireland 23 years ago, Mr Ghai said it was not much of a shock culturally, but the weather did take him by surprise.

“Three seasons in a half hour,” he said, adding that a major decision in Indians choosing Ireland was not just because of the thriving economy but because of safety.

“People feel safe to stay here,” he said. “It is a lot safer than anywhere else.”

Despite the concerns around a surge in anti-immigrant rhetoric, he has not encountered any prejudice but was aware others may not be as fortunate.

As for people being stereotyped, he said: “You will always get that, anywhere.”

The latest census found that over half of those living in Ireland with an Indian background were aged between 25 and 44 years.

Along with significant recruitment in hospitality, workers from India have also been drawn to jobs in the health, tech and banking sectors.

There has also been an upward trend of Indian students coming to study at third level.

India’s ambassador to Ireland, Akhilesh Mishra, said in the aftermath of Brexit, Ireland has gained significant attraction among students seeking “high quality” university education.

He also said with a Taoiseach of Indian heritage, it has enhanced the profile and visibility of Ireland in India and now it’s viewed globally “as a highly diverse and pluralistic, inclusive society.”

He said the Indian diaspora has noticeably increased in the last two to three years with an estimated 80,000 now living here.

In contrast, the number of Polish people choosing to live in Ireland fell. In 2022, it had fallen by 24% compared with the 2016 census, a decrease of almost 29,000 people.

However the community remains the largest group of non-Irish citizens.

Polish artist Kate Kos, who has been living in Ireland for close to two decades, said she was asked the question, “Where do you come from?” so often that it would get frustrating.

She changed her name from Katarzyna to Kate for easier integration but added that her accent keeps the curiosity around her origins.

Nevertheless she said life had been rewarding from her initial work in horticulture to now having her own art gallery.

She came from a village near Krakow to Co Wexford with a friend after Poland joined the EU in 2004.

It was not long after that she decided to make it a permanent move, enamoured by Ireland’s nature and people.

There have been a few disdainful comments including “go back go where you come from” uttered at her at times, but she said that is a minority view and she felt very much part of the community in Gorey.

While home for her is Ireland, she has seen others return to Poland.

Krzysztof Kiedrowski of the Irish Polish Society said a “booming” economy in Poland along with cheaper rents were some of the incentives for people to consider a move back to their native country.

The Polish Embassy in Ireland confirmed this has been happening for several years.

A spokesperson said Polish people were moving out of Ireland due to the impact of the cost-of-living crisis and “without any imminent end” in sight.

It also cited the welfare programmes in Poland that were helping families and enticing them to return home.

Mr Kiedrowski said Poland is how Ireland was in 2004 when he first left, referring to the abundant employment opportunities that were now available.

He added that they remain “very strong Catholics like Ireland used to be”.

For the Polish communities who have stayed and are immersed in Irish society, he said there were numerous events and outlets that were “keeping our culture” alive, helped also by the array of shops with local products available.

While the number of Polish people in Ireland dipped to below 100,000, Polish remains the most spoken foreign language.

Multilingualism is flourishing generally with more than 750,000 people speaking a language other than English or Irish at home, an increase of 23% from 2016.

Dorina Steele, a beautician from Moldova said she enjoys hearing her native Romanian language being spoken daily in Blanchardstown, where she lives.

The mother of two said it was a challenge adapting to Irish life and a new language when she arrived in 2014.

One in five people living in Dublin city are non-Irish citizens.

Ms Steele said she embraces being part of that diversity while also observing the contrasts between her Moldova and Ireland.

“The cuisine, medicine and much less homework” were the main differences she said.

Irish people generally know very little about Moldova, she said, but added that she is always keen to share information about it.

“I have to explain it’s between Ukraine and Romania,” she said. “I am happy that in school the children are now having culture day and promoting different cultures.”

The Immigration Council of Ireland said it is important to invest in diversity.

Chief Executive Officer Brian Killoran said the phenomenon of migration brings challenges but he also highlighted the importance of dismissing the “voices of those who encourage people to fear migrants” and those “who paint a false narrative that they are taking more from Ireland than they are giving”.

He said migration supports the development of Ireland in ways that were “unimaginable” in the past and warned of an “immense need” to future-proof approaches to it.