To have one Government collapse because of your budget proposals may be regarded as a misfortune; to have it happen a second time might look like carelessness.

In fairness John Bruton – whose death was announced this morning – could never be accused of carelessness, while others bore at least as much responsibility for the fall of the two governments concerned. What he lacked – despite his many political gifts – was luck.

Until, at what seemed to be the last moment, his luck turned and he became Taoiseach in the most unlikely of circumstances.

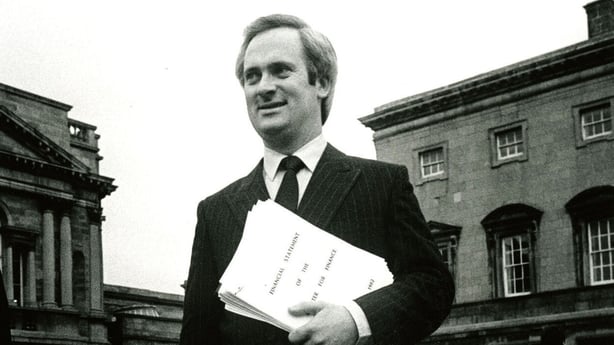

The first, and better known, of his two budgetary mishaps demonstrates this bad luck. In June 1981, at the age of just 34, Bruton was appointed Minister for Finance in Garret FitzGerald’s first government. The two men had big plans for what they wanted to do – plans which had to be jettisoned once they got a look at the books and realised just how bad the State’s financial position was. The true position had been covered up by the outgoing Fianna Fáil government, but the unpleasant news was broken to FitzGerald and Bruton, causing an agonising reappraisal of what was possible.

Bruton later related a real fear that unless the finances could be brought under control, the Government would be unable to borrow money, which would lead to the IMF being called in and Ireland losing its economic sovereignty – as would in fact happen 30 years later.

Bruton was determined to take action, and did so with a supplementary budget in July which raised indirect taxes and imposed a one per cent income levy.

We need your consent to load this comcast-player contentWe use comcast-player to manage extra content that can set cookies on your device and collect data about your activity. Please review their details and accept them to load the content.Manage Preferences

Unpopular moves, but it was the following January’s full Budget, and a proposal to impose VAT on children’s shoes, which caused Independent TD Jim Kemmy to withdraw his support, leading to the collapse of the government.

John Bruton got most of the blame, then and since, for a decision that was beyond his control. Labour had refused to accept the abolition of food subsidies, prompting the decision to increase VAT instead, while the civil service insisted that children’s shoes couldn’t be excluded from VAT because it would be impossible to distinguish between large-size children’s shoes and small-size women’s shoes.

We need your consent to load this comcast-player contentWe use comcast-player to manage extra content that can set cookies on your device and collect data about your activity. Please review their details and accept them to load the content.Manage Preferences

A snap election returned a minority Fianna Fáil government, and Fine Gael returned to Opposition – though not, as it turned out, for long.

The children’s shoes debacle was a set-back to Bruton’s previously flawless rise through the political ranks. From a wealthy farming background in Meath, he was attracted to Fine Gael by the Just Society policy of Declan Costello, and was first elected to the Dáil in 1969 – at 22, he was the youngest member of the 19th Dáil.

He was a Parliamentary Secretary in the National Coalition from 1973 to 1977, and was brought onto the Fine Gael opposition front bench by Garret FitzGerald before getting the plum Finance portfolio in Government, with, as we have seen, dramatic consequences.

When Fine Gael returned to government in December 1982, John Bruton did not return to Finance, being appointed to the Department of Industry instead. He was also Leader of the House, responsible for Dáil reform.

His time in Industry was marked by a difficult relationship with the junior coalition partner, the Labour Party, including a row over Dublin Gas that led to the resignation from government of Frank Cluskey. His poor relations with Labour would come back to haunt him.

In 1986, a Cabinet reshuffle saw him return to the Department of Finance, replacing Alan Dukes. But his proposals for the following year’s Budget were rejected by Labour ministers, who had had enough of austerity. Again, bad luck – Bruton’s proposals did not differ from what Dukes would have proposed. He was just in the wrong place at the wrong time, and a second Bruton Budget went down in flames.

This hardly improved his chances in the leadership election when Garret FitzGerald stood down after losing the 1987 general election. Alan Dukes won that contest. But after a disastrous Presidential election campaign in 1990, he in turn resigned and John Bruton was elected unopposed as the eighth leader of Fine Gael.

The new leader found it difficult to make his mark, consistently being outshone in the Dáil by Labour’s Dick Spring. Attempts to widen Fine Gael’s appeal – including a disastrous “comedy” sketch featuring Twink at a party conference – backfired.

The collapse of the Fianna Fáil-Progressive Democrats coalition in late 1992 led to an election – but the opportunity was seized by Labour, rather than Fine Gael. While Fine Gael returned with 45 seats, down ten, Labour more than doubled its number of seats to 33, up 18.

Once again, Bruton’s luck was out, and as the results came in, former Fine Gael presidential candidate Austin Currie suggested Dick Spring should become Taoiseach at the head of a new Coalition.

This did not go down well with Bruton who was, after all, the leader of the larger party. He wanted a three-way coalition with Labour and the Progressive Democrats. This did not appeal to Labour which preferred Democratic Left as the third element of the coalition. Such a left-leaning government was not attractive to Fine Gael, and would not have had a Dáil majority.

In the event, wary of involvement with the PDs, and remembering poor relations with Bruton in previous governments, Spring opted instead for coalition with Fianna Fáil. That government had a massive Dáil majority, and was boosted by the peace process, which led to the IRA ceasefire in August 1994.

Although Bruton survived a leadership heave in February 1994, it seemed that his moment had gone; there appeared to be no prospect of returning to government any time soon.

And then… his luck changed.

The relationship between Taoiseach Albert Reynolds and Tánaiste Dick Spring had been crumbling; a row over the report of the Beef Tribunal nearly caused the coalition to collapse, but it was disagreement over the appointment of Attorney General Harry Whelehan to the High Court that caused Labour to pull the plug.

By-elections had changed the arithmetic in the Dáil, making a Fine Gael-Labour-Democratic Left coalition possible. And so, on 15 December, 1994, John Bruton was elected Taoiseach at the head of a three-party “Rainbow Coalition”.

One of the main issues facing the new government was the faltering peace process, with progress towards inclusive talks stalled over the issue of IRA decommissioning.

John Bruton detested the IRA’s use of violence and distrusted Sinn Féin – and he made little effort to hide his views.

In July 1995, he wrote a private memorandum setting out his views on the process, brimming with distrust of republicans and foreboding about the future. “My primary worry is that the Irish Government will become, or is already becoming, a hostage to Sinn Féin’s line on the shape of the political/talks process. Sinn Féin hold all the cards and the Government holds none.”

As he predicted in the memorandum, he and his government attracted some of the blame when the IRA broke its ceasefire in February 1996. But to Bruton, the resumption of violence proved that the IRA and Sinn Féin could not be trusted.

Bruton’s dislike of Sinn Féin was fully reciprocated, and he was viewed by some as too pro-Unionist (Albert Reynolds once referred to him in the Dáil as “John Unionist”, an apparent Freudian slip).

His critics might have been surprised to learn that Bruton could stand up to London when he felt he had to – a furious row with John Major in July 1996 saw the British Prime Minister threatening to hang up the phone on the Taoiseach.

He also cancelled a planned summit with Major, and refused to set a new date, until the British agreed to a less hardline position on decommissioning.

The Taoiseach had a short fuse on occasion. Sometimes this had positive results – his annoyance at a Christmas traffic jam led to Operation Freeflow, which saw cars illegally parked in clearways actually being towed away.

At other times, it was a liability – such as when he had to apologise after telling a reporter he was “sick of answering questions about the f***ing peace process”.

John Bruton was often seen as conservative on social issues, so it came as something of a surprise when he identified the introduction of divorce as one of his key priorities when he was elected Fine Gael leader in November 1990, arguing that the law should reflect social reality.

The Rainbow Coalition put a divorce referendum to the people in November 1995, and as Taoiseach, he made what was widely regarded as a decisive intervention on the Sunday before polling on the This Week radio programme on RTÉ. The proposal was accepted by a tiny margin – just half of one per cent.

A year later, in November 1996, the coalition was rocked by the resignation of Fine Gael’s Michael Lowry after revelations about his business affairs. The controversy damaged both Bruton and Fine Gael, and also led to the establishment of the McCracken Tribunal which investigated payments to politicians by Ben Dunne and Dunnes Stores – a Tribunal which made public a series of payments to former Taoiseach Charles Haughey.

Overall, the Rainbow Coalition proved surprisingly harmonious. Labour ministers who remembered their previous experience in government with him were impressed by the chairmanship of the Taoiseach.

With the economy growing rapidly, and unemployment and government debt falling, the Rainbow faced the June 1997 election with some confidence. But Fine Gael seat gains couldn’t make up for significant Labour losses, and John Bruton once again became leader of the opposition.

Facing a popular government benefitting from an economic boom, Fine Gael lost ground in opinion polls, and once again turned on its leader.

He survived a motion of no confidence in November 2000, but just two months later, another leadership challenge was mounted – this time successfully.

However, his political career wasn’t over just yet – in September 2004 he was nominated as the EU Ambassador to Washington, a position he filled for five years.

Throughout his political career, he relied on the support of his wife Finola. They married during his first term as Minister for Finance in September 1981, and had four children.

In retirement, John Bruton continued to comment on public affairs, particularly on Europe, and formed an effective double act with his former rival Bertie Ahern in warning Britain of the implications of Brexit.

He remained an original thinker, with strong opinions and a dedication to public service.

There will be a special RTÉ News programme on John Bruton at 11am on RTÉ One and the RTÉ News channel.

Source link

TG4 TV PC to TV

TG4 TV PC to TV