Why did Poland get rid of homework in primary schools?

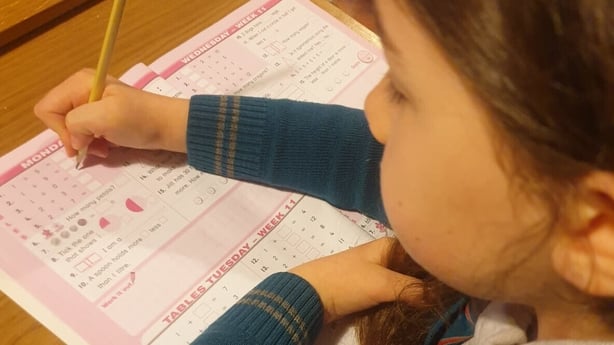

Nine-year-old Franek Duś from the southern Polish town of Tarnowskie Góry loves Real Madrid and wants to be an engineer when he grows up.

Franek used to spend two hours per evening doing his homework but, since the start of this month, he is one of 3.1 million primary school pupils in Poland who no longer has to open his books when he gets home from school.

That is because the Polish government has dispensed with compulsory homework for primary schools.

“It’s just cool and you have more time for your hobbies, like playing football and meeting friends,” Franek told RTÉ News.

His mother, Ewa Duś, is relieved too.

“I think it’s a great idea because we had already discussed during meetings at school that there was way too much homework,” said Ms Duś.

“He seems more happy and I see that the atmosphere at home is way better,” she said.

Prime Minister Donald Tusk’s centre-right Civic Coalition, which makes up the largest group within a four-party pro-EU coalition government, had promised to scrap homework at primary school level during last year’s general election campaign.

Critics of the current curriculum argue that it is overloaded with content and that homework was taking up too much of children’s free time after school.

Four months after the government’s formation, the party followed through on its promise to cut homework.

Education minister Barbara Nowacka said, in March, that the new rules will give students “more time to consolidate their knowledge, prepare for tests, read books, and, more importantly, pursue their passions and rest”.

Ms Nowacka also said that the new rules will create a “level playing field” for students.

“It is very common for children to do homework with their parents. Not all parents have the competence to learn mathematics, chemistry and physics with their children,” she said in February.

Children in Poland attend primary school from ages seven to 15, after four years of preschool which begins at three years of age.

The new regulations mean that homework is now off limits for grades one to three when pupils are aged seven to 10.

For grades four to eight, when students are typically 11 to 15 years old, teachers can continue to issue homework but it cannot be graded, and it is not compulsory for students to complete the tasks either.

Exercises that improve fine motor skills such as painting and hand-writing practice are still compulsory.

Poland’s ministry of education issued schools across the country with guidelines on how to implement the changes but, coming in the middle of the academic year, the change still took many teachers and parents by surprise.

“The decision to limit homework was done too rashly,” Slawomir Broniarz, the President of the Polish Teachers Union (ZNP), told RTÉ News.

The union, which represents more than 200,000 Polish school teachers, is not against the decision to stop homework for the first three years of primary school, but still sees benefits in assigning children practical tasks at home such as improving their writing skills.

However, Mr Broniarz believes that homework should still be given to older pupils in grades 4 to 8.

“Homework teaches responsibility, commitment and teaches how to plan your own time. It is also a way for teachers to observe what students learn from their classes,” he said.

A number of education experts in Poland view the government’s decision as a first step towards rebalancing a curriculum that is already overloaded with a lot of content.

Some teachers, often short of time to teach everything on the syllabus within class hours, were using homework as a way of covering material.

Another Polish student I spoke to, 13-year-old Tomek Dzieciolowski from Warsaw, was not so thrilled about the new no-homework policy.

“In my opinion, it’s a stupid idea because homework was a way of teaching kids,” said Tomek, who used to spend around 30 minutes per day on his homework.

“It’s kind of a big change because now you can’t get any grades also from projects.”

Tomek’s mother, Justyna Rutkowska, said that the “whole thinking” towards education in Poland needed to change and felt that banning homework alone was not the solution.

“The compulsory material is overloaded, there is too much. Teachers have no time at school to fulfil it,” she said, adding that reading material was skewed towards Polish classical literature that has little to do with children’s experiences today.

Surveys show that teachers in Poland overwhelmingly favour retaining homework, though many, like Mr Broniaz, agree that the volume of homework should be reduced in primary schools.

“Polish students are overwhelmed by the amount of work,” he said.

Tom McGrath, the principal of the British Primary School in Warsaw and a native of Co Limerick, told RTÉ News that homework has a valuable role in “reinforcing” material taught in the classroom without it becoming “overly burdensome”.

The new rules in Poland on homework, he believes, are “a signal of intent” from the Polish government of “a change in style and, eventually, substance” towards creating a skills-based curriculum, that is more holistic in its approach.

Poland’s education system is no stranger to sudden changes.

The country’s previous nationalist Law and Justice government, which ruled from 2015 to 2023, brought back the current 8-year primary school system from ages 7 to 15, which had been scrapped in 1999.

In the interim, a middle school system had been in place.

However, such changes to the school system do not appear to have had a negative impact on the performance of Polish primary school students, who score high on PISA tests, the international study used to assess the education levels of 15-year-olds in OECD countries.

The tests measure performance in maths, reading and science, and more students in Poland, than on average across OECD countries, were top performers in at least one subject according to data from 2022.

15-year-olds in Ireland also scored above the OECD average in all three subjects, and ace reading tests in particular.

In Finland, where children also start formal primary school at seven, teachers set very little compulsory homework. Yet, Finnish students are top performers on PISA tests.

There has been some discussion in Ireland in recent years too over whether homework is beneficial to children’s educational development.

Lorraine Harbison, an associate professor at DCU who focuses on primary school mathematics teaching, said that homework is used “for reward or punishment, which isn’t good to even to begin with”.

Ten years ago, she co-authored a limited study on the utility of homework in Irish primary school classrooms.

The study found that “homework that is too difficult and too long to complete, or is seen to be inappropriate or of no relevance to the child, may actually have an adverse effect”.

Ms Harbison said she favoured more project-based homework that encouraged pupils to “work skillfully” and to “read for understanding”.

The Department of Education does not issue schools with guidelines on how much homework is appropriate.

In a reply to TD questions in February 2021, at the height of Covid-19 pandemic, Minister for Eeducation Norma Foley wrote: “It is a matter for each school, at local level to arrive at its own homework policy. In keeping with good practice, the process of drafting a homework policy should involve consultation with teachers, parents and students”.

Taking those comments onboard, it seems that Irish schools have a lot of leeway to experiment with different approaches to homework, provided that parents are supportive of any plan.

In Ireland, pupils’ views towards homework becomes more negative between 4th and 5th class, from ages nine to 11.

That is according to an ongoing study by UCD’s School of Education entitled the Children’s School Lives project, which is following the experiences of 4,000 children across Ireland as they progress through primary school.

Homework is one pillar of the study, which is expected to conclude in 2026.

By 5th class, about half of primary school students surveyed held a negative view towards homework.

This change in attitude occurs at a time – the end of the primary system in Ireland – when teachers also expect pupils to be capable of completing more homework tasks.

The same study found that parents of primary school pupils in Ireland hold overwhelming positive views towards homework.

“For parents, they see homework as an important indicator of how their children are doing in school,” said Dympna Devine, Full Professor of Education at UCD’s School of Education, who leads the study.

It is far too early to know if Poland’s decision to limit homework will bring positive benefits for children.

“It is not an opportunity for children to sit down at the computer or a console with games,” said Mr Broniaz, the president of the Polish teacher’s union.

He thinks that schools could play a role in providing a space for children to use their free time.

Since the homework ban came into effect in Poland earlier this month, there have been reports of parents asking teachers to continue giving homework.

But most children are enjoying their extra free time in the evenings.