Why bonfires blaze across Ireland on June 23rd

Analysis: the sight of St John’s Eve bonfires on hilltops still provides quite a spectacle and reminds us of a pivotal time in the calendar

Since the distant past, bonfires lit by humans at midsummer greeted the sun at the height of its powers in the sky. The accompanying ritual celebrations were primal, restorative, linked with fertility and growth. Midsummer and the time around St John’s Day have been traditionally celebrated throughout Europe.

In Ireland, we’ve had a dual tradition of conventional Christianity running alongside older folk religions. The year was marked with Christian festivals applied as thin veneers over the ancient underlying (so called) Celtic calendar, which originated in something much older and mysterious.

St John’s Eve is a typical Christian front applied to the folk celebration of the summer solstice which occurs around the 21st June, the longest day of the year. The actual Feast of St John the Baptist falls on the 24th June (known as midsummer day), and ‘Celtic’ festivals start at sundown on the evening before the feast day, when the major festivities occur. It’s an event known as Bonna Night in Cork.

We need your consent to load this rte-player contentWe use rte-player to manage extra content that can set cookies on your device and collect data about your activity. Please review their details and accept them to load the content.Manage Preferences

From RTÉ Radio 1’s Today With Sean O’Rourke in 2017, folklorist Michael Fortune discusses St John’s Eve traditions

While gathering around a community bonfire was a chief part of St John’s Eve well into living memory, the custom has become unknown in some regions. To this day though, bonfires blaze on hilltops in some areas and the sight of them still prove quite a spectacle, reminding us of the pivotal time in the calendar.

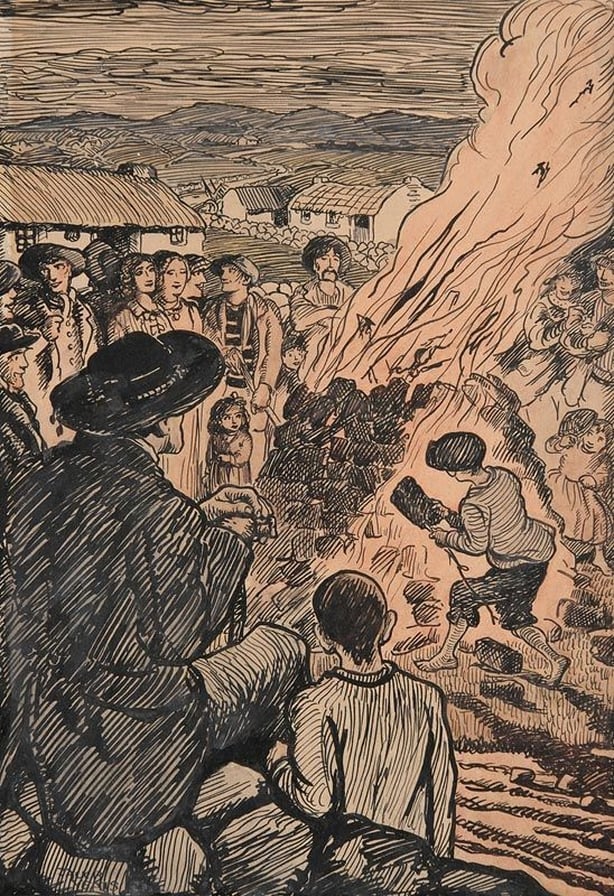

A visual spectacle

For the St John’s Eve bonfire, a spot was chosen at a high vantage point so that it could be seen and it tended to be the same location every year. The visual aspect of the bonfires on every hilltop was important. Writing in the 1820s, Thomas Crofton Croker described St John’s Eve: ‘the effect produced by fires lighted early in the evening on the highest points of the surrounding [landscape…] was very impressive”.

Young and old were involved in gathering fuel for the fire; turf, furze, old hay and any waste materials were collected. Old bones were considered good fuel as these would burn for a long time (the word bonfire has its origins in ‘bone fire’). As with other European bonfire customs, people would preserve bones specifically to be burned in the bonfire, especially those of animals who had been sick, in the hope that it would somehow purify the rest of the herd of disease.

We need your consent to load this rte-player contentWe use rte-player to manage extra content that can set cookies on your device and collect data about your activity. Please review their details and accept them to load the content.Manage Preferences

From RTÉ Archives, Ciarán Mac Mathúna’s Fires of St John: Midsummer in County Clare reports on St John’s Eve boinfires and traditions near Spancil Hill in Co Clare

Processions, food and cures

There were often processions to the bonfires, with applause and cheering as the fire was lit around sunset. It was notable as a community get-together usually with no appointed leaders, religious or secular, and the fire was responsibly managed.

The midsummer bonfire was associated with luck and purification, and the tangible remains of the ashes were thought to be good fortune and spiritual cure for the year ahead. As the fire burned, a treat called ‘goody’ was served for the occasion in some regions: it was a mixture of bread in hot milk with sugar and spices. Early potatoes were sometimes roasted in the fire and shared.

Obtaining a light from the bonfire was considered lucky and whoever came home first with the ‘sacred’ fire was thought to bring the good luck of the year with them. Jumping through the bonfire was a common custom. A farmer might do this to ensure a bigger yield for his crops or livestock, while engaged couples would jump together as a sort of pre-wedding purification ritual. Single people jumped through in the hope it would bring them a future spouse.

Finally, the fire was raked over and any cattle not yet at the summer pasture were driven through the smouldering smoke and ashes to ensure good luck. The remaining ash was scattered over crops or could be mixed into building materials to encourage good luck in a building. The ash was considered curative too, and some mixed it with water and drank as medicine. Embers were brought into the house as protective talismans.

Bonfires in Irish folk tradition were a chief feature of both St John’s Eve and Bealtaine (May 1st) but there were some differences. St John’s Eve was a regular working day usually with communal bonfires lit only after the day’s toil was complete, while Bealtaine was a day off with both community and home bonfires in most areas.

On St John’s Day itself, holy wells were visited and some fairs were held. It was believed herbs gathered on St John’s Day itself had an extra potency and would be reserved for use in folk medicine and divination, such as St John’s wort, foxgloves, mugwort and yarrow. It was customary for people to take their first swim of the year at this time. People predicted the weather too at this time of year with one saying predicting “Midsummer rain spoils hay and grain”.

In some parts of Ireland, bonfires were lit on the Eve of Saints Peter and Paul (June 28th) instead of St John’s Eve. The tradition was known in the east and south-east of the island and in some parts of the country it was known as Little St John’s Day.

We need your consent to load this rte-player contentWe use rte-player to manage extra content that can set cookies on your device and collect data about your activity. Please review their details and accept them to load the content.Manage Preferences

From RTÉ Archives, Stella Carroll reports for Nationwide in 2002 on the rituals and rites associated with Ireland’s holy wells

Ancient fires and sun worship

As ceremonial bonfires are part of archetypal pre-Christian rituals (as depicted in films from The Wicker Man to Midsommar), one might wonder how long our ancestors have been lighting them to mark midsummer. Although there have been some examples of urban St John’s bonfires, they are predominantly rural and seem intrinsically linked with agriculture. It may be the case that comparable rituals were found in early farming communities in Ireland.

The solstices represented key points in the farming calendar, and the summer solstice marked the time when the sun was at its height in the sky. The sun was the governing force that ruled the lives of people in the ancient world. As far back as the 5th Century, St Patrick alluded to people who worshipped the sun and not Christ.

In Irish Heritage, Estyn Evans speculated that midsummer fires were lit from ancient times to keep the sun, now at its highest point and about to decline, on its course. By the 19th century, as Thomas Crofton Croker noted, the feast was not for St John but ‘a popular custom of remote antiquity and a remain of pagan rites in honour of the sun’.

Going further back, there is evidence that some Neolithic monuments were aligned to sunrise and sunset at certain times of the year. Newgrange is the most well-known astronomically aligned monument in Ireland, and several other Neolithic tombs appear to have an intentional placement with the sun, such as Townleyhall (near Newgrange) which is a summer solstice ‘sunrise’ alignment. Cairn G and Cairn H at Carrowkeel in Co. Sligo are also loosely summer solstice ‘sunset’ aligned.

Midsummer bonfires offered an opportunity to salute the light of the superessential sun, and were both a celebration of and devotion to the natural world. The St John’s Eve bonfires that continue today – managed under controlled circumstances as they were in the past – echo our ancestors’ feeling of optimism, good fortune and continuation, and remain a valuable part of our cultural heritage.

Follow RTÉ Brainstorm on WhatsApp and Instagram for more stories and updates

The views expressed here are those of the author and do not represent or reflect the views of RTÉ