West Bank paying heavy toll while focus is on Gaza

In the early hours of 19 October, the Mahameed family heard a commotion outside.

Taha, the 15-year-old son, crept out of their crudely built residence down to the main street below, peering up to his right at the source of the noise, an Israeli Defence Forces (IDF) raid.

His sister, 18-year-old Sima, urged Taha not to leave their home, watching anxiously from the first-floor window, she instinctively took out her phone to film the scene.

There is a sudden burst of gunfire and Taha falls heavily to the ground. On the recording, Sima screams as her family cries out in panic.

Seconds later her father Ibrahim runs out to his son. He too is shot by unseen figures. He falls, but manages to stagger back to the building.

The ambulance arrives, but Taha dies a few hours later.

His father dies of his injuries on 8 March. Neither were armed nor posed a threat to the security forces, according to the footage.

This week, in the Nur Shams refugee camp to the northwest of the West Bank, Sima and her younger sister Sara reflect on the international community’s determination to steer the Israeli-Palestinian conflict to a solution where two states might one day live in harmony, side by side.

“No, never,” says Sima bitterly.

“They took over our land. They are killing us. We will never live together.”

Nur Shams has a population of 13,000 squeezed into a dusty, rubble-strewn 0.21sqkm hollow, overlooked by a tree-lined, rocky hill.

The UN agency for Palestinian affairs describes a community blighted by overcrowding and high unemployment.

“An open sewerage channel runs from Nablus to Tulkarm bordering the camp,” a UNRWA report states. “In winter, the sewage flow swells due to rainwater.”

Since 7 October, the greatest threat is not from sewage flows but IDF raids, which are characterised by killings and the demolitions of homes of suspected militants.

The night Taha died, an Israeli drone killed four children and eight men, according to Al Jazeera, with one IDF officer killed by an explosive device.

In all, since 7 October there have been 12 raids resulting in 39 deaths, including the killing of two suspected militants in an airstrike two days after we visited Nur Shams.

There is certainly no shortage of Palestinian fighters.

Banners showing uniformed “martyrs” adorn the alleyways, their smiling faces floating above the golden dome of the Al Aqsa Mosque in Jerusalem.

One young Islamic Jihad member agrees to talk to us, echoing Sima’s rejection of a two-state solution.

“They took our land,” he tells RTÉ News. “We will get it back, with the will of God. I can see the gates of Jerusalem opening to us.”

To the IDF, Nur Shams is a straightforward terror threat.

During a raid on 19 January, troops “scanned around 1,000 buildings and located more than 400 explosive devices, and seized 27 weapons and other military equipment.

Five explosive manufacturing labs and four sites used by local terror operatives to observe Israeli forces using surveillance cameras were also located and destroyed,” according to the Times of Israel.

While the focus of the world is on Gaza, the West Bank has been paying a heavy toll.

“There is another war going on in the West Bank,” says Sabri Saidam, deputy secretary general of the Fatah Central Committee in Ramallah.

“It is quieter behind the scenes but it’s no less atrocious.”

Some 435 Palestinians have been killed in the West Bank by the IDF or violent settlers since 7 October.

Jewish settlements are expanding and confiscation of Palestinian lands are increasing at a greater rate than at any time since the 2000s, according to the West Bank Protection Consortium (WBPC), a group of EU member states, including Ireland, as well as Canada and Norway.

Around 145 settlements and 100 outposts, considered illegal under international law, now populate the West Bank.

They represent a formidable impediment to a contiguous Palestinian state, which is, by common consent across the international community, the US, Europe, the Arab world and China, the only real pathway out of the darkness.

“The reason for this revival is not complicated,” writes Martin Indyk, a former US ambassador to Israel and who was closely involved in the conflict in the Clinton and Obama administrations.

“There are, after all, only a few possible alternatives to the two-state solution.

“There is Hamas’s solution, which is the destruction of Israel. There is the Israeli ultra-right’s solution, which is the Israeli annexation of the West Bank, the dismantling of the Palestinian Authority (PA), and the deportation of Palestinians to other countries.

“There is the ‘conflict management’ approach pursued for the last decade or so by Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu, which aimed to maintain the status quo indefinitely—and the world has seen how that worked out,” he wrote in an article for Foreign Affair.

Are we perhaps in the darkest hour before the dawn of a revived peace process?

Palestinian officials believe Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu wants to expel the Palestinians from Gaza, starting with an assault on Rafah, and then to push them out of the West Bank through settlement expansion.

“We are going to see a much darker hour if Netanyahu proceeds with his plan,” says Mustafa Barghouti, a veteran negotiator and currently general secretary of the Palestinian National Initiative.

“Without removing illegal settlements from the West Bank, you cannot have a Palestinian state. The whole talk about a two-state solution is [therefore] only camouflage for doing nothing, for sustaining the status quo,” says Mr Barghouti.

In Palestinian villages being squeezed by settlement expansion, it does not exactly feel like the status quo.

We drive north out of Jerusalem, weaving our way through the sandstone-ribbed Samarian Hills, alternately passing settlements, whose residents enjoy exclusive access to the smart motorway heading south to Jerusalem, and ramshackle hilltop Palestinian villages, blocked from using the road so that journey times quadruple.

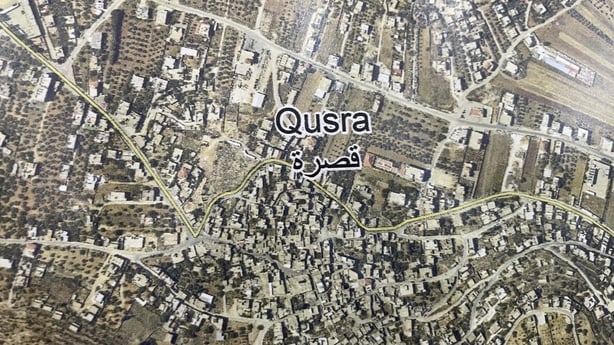

We arrive in Qusra, a Palestinian village locked in an increasingly deadly cycle of violence from Jewish settlers.

In his office, mayor Hani Odeh shows on a map how three Jewish settlements, Esh Kadesh, Akiya and Kida, are encircling Qusra, with smaller outposts also springing up rapidly nearby.

The establishment of “wild cat” settlements involves a settler simply parking a caravan on a piece of land.

One or two other caravans will arrive, then fencing will appear around the site, with electricity and water lines established soon afterwards.

Once the new site takes shape, an Israeli military outpost will appear nearby.

Palestinians who want to challenge what they see as the theft of their land have little or no legal recourse, and if a confrontation turns violent, the IDF will side with the settlers.

“Of course, it’s a plan to expel the Palestinians into Jordan,” he tells me.

“There are no jobs, there is no income. They want to throw us out. A lot of people now go to the American embassy to apply for visas, 30, 40 people from our village – and they never come back.”

Settler expansion is part of a debilitating process in which the deck is stacked heavily against the Palestinians, thanks to Israel’s tight security and administrative grip on the West Bank.

Under the 1993 Oslo Accords, the West Bank was divided into three zones, A, B and C.

The first two made up 40% of the geographical area of the West Bank and contained 2.8 million Palestinians.

Area C is territory outside A and B, which was supposed to have been gradually transferred to the Palestinian Authority (PA), pending negotiations that would settle the conflict.

However, Israel has steadily reclaimed Area C and it is now completely under its control, not just in terms of security, but also civil affairs, planning, building, infrastructure and development (Israel’s rationale is that this is to prevent Palestinian terror attacks).

Such planning laws are heavily weighted in favour of settlers and against Palestinians.

Israel, say non-governmental organisations, has designated large parts of Area C state land in order to prevent Palestinians building on it, while land not designated as “state-owned” is also off limits through arbitrary restrictions.

As a result, only 1% of Palestinian planning applications are granted in Area C, even on privately owned land, while Jewish settlers are readily given approval to build on land they have taken.

“Israel uses its planning regime to effectively ensure Area C is completely hostile territory for Palestinians,” concludes a report by the West Bank Protection Consortium.

It adds: “A place where they should neither live nor thrive – with the aim and effect of pushing Palestinians off the land and into the overcrowded and the less resource-rich areas of the West Bank [ie, areas A and B], and so that Israel can annex Area C and thus have access to its abundant resources.”

A necessary corollary of settler expansion appears to be the shrinking of Palestinian land through confiscations, the stunting of village growth and the blocking of access to roads and farmland.

That fact of life is made worse by settler attacks.

Locals complain about the uprooting of olive trees, the burning of chicken coops, and the demolition of Palestinian homes and schools by settlers, who claim that the buildings do not have permits.

In December, ten homes and a school funded by the EU and Irish Aid were demolished in Khirbet Zanuta, prompting a sharp rebuke from the EU’s crisis management commissioner Janez Lenarčič and later from President Michael D Higgins, who said it was “further evidence of the appalling impact” the violence was having on the lives of children.

Four days after the 7 October attacks, settlers raided a house on the edge of Qusra.

The mayor called for help using the mosque’s PA system and when a group of men responded a firefight ensued and the Israeli military appeared with sirens and guns blazing.

Four Palestinians were shot dead, including Murad Odeh (his cousin Mahmoud went to his rescue and was himself shot in the back).

During the funerals the following day, mourners were attacked again, and two men, a father and son, were shot dead.

Locals say settler and IDF violence is indistinguishable.

“Whatever they want to do they do,” says Mahmoud. “When they want to kill they kill, when they want to arrest you they arrest you, they can do whatever they want.”

While the conflict has increased since 7 October, settler expansion appears to have been boosted by the rise in the religious right, who believe they have an Old Testament and God-given right to the West Bank.

In a 2017 essay, Belazel Smotrich, the leader of the Religious Zionist Party, wrote: “Nothing would have a greater and deeper effect on the consciousness of the Arabs of Judea and Samaria [ie, the West Bank], deflating their illusions of a Palestinian state and demonstrating the impossibility of establishing another Arab state west of the Jordan.

“Facts on the ground deflate aspirations and defeat ambitions. Let the settlement blocs attest to this.”

In November 2022, Mr Netanyahu appointed Smotrich finance minister, with responsibility for administering a large part of the West Bank, where Palestinians fear he is putting his 2017 essay into action.

Against this backdrop, the two-state solution had begun to look fanciful to say the least before 7 October.

The Oslo Accords, agreed in 1993, envisaged a Palestinian state in 97% of the West Bank and all of Gaza, with mutually agreed land swaps that would compensate the Palestinians for the 3% of the West Bank Israel would annex (at the peak of the Oslo Process that 3% contained 80% of all Jewish settlers).

The Oslo Process fell apart in 2000 over the issue of a Palestinian capital in East Jerusalem and the return of refugees.

Palestinians launched the Second Intifada and Jewish settlements increased. Distrust, violence and polarisation escalated and successive US administrations lost the energy to revive a peace process.

Benjamin Netanyahu tacitly kept Hamas in place in Gaza in order to weaken the Palestinian Authority in the West Bank, allowing him to tell international partners he had no partner for peace.

He then embarked on a normalisation process with Arab states over the heads of the Palestinians, culminating, under the Trump Administration, in the Abraham Accords which favoured trade links between Arab countries and Israel, but demanded little by way of helping create a Palestinian state.

President Biden continued with this policy in the hope that a breakthrough normalisation agreement between Saudi Arabia and Israel was within reach.

In fact, it was within reach – right before 7 October.

Now the two-state solution is back in vogue in international diplomacy, which is why the Biden Administration has been tacitly hinting at the replacement of Benjamin Netanyahu for starters, something Palestinians are desperate for.

“Everyone is watching desperately to see how we can break the cycle and get rid of Netanyahu,” says Saidam Sabri, of the Fatah Central Committee in the West Bank.

“Even Biden is saying it, and the international community is recognizing that there is a bunch of lunatics in Tel Aviv that are running the situation.”

Yet Israeli and Palestinian public opinion is hardening and polarising.

On the Israeli side, a poll by the January Peace Index at Tel Aviv University found that 88% of all voters believe the scale of Palestinian casualties is justified, given the government’s war aims, while 48% are “very much opposed” to peace negotiations with the Palestinian Authority, compared to just 2.1% who are “very much in favour”.

On the other side, there are some complex findings.

The Palestinian Centre for Policy and Survey Research found on Wednesday that 71% of Palestinians in Gaza and the West Bank believe Hamas was correct to launch its 7 October attacks.

While 94% believe Israel is responsible for war crimes, only 5% believe Hamas has committed such crimes.

Yet, despite Israel’s vow to eliminate Hamas, 59% of Palestinians believe the organisation will remain in control of Gaza after the war.

Asked if they were in favour of a two-state solution, based on a US and Arab effort strengthening the Palestinian Authority and normalising Arab-Israeli relations, some 73% of Palestinians were opposed to the idea (although more Gazans favoured it than those in the West Bank).

In a tour of Kibbutzim in southern Israel, in which scores of Israelis were killed by Hamas on 7 October, there was an overwhelming view that Hamas started a war that Israel did not want, that Israel had wanted Gazans to live in peace, and that Israel was facing an existential threat, and a foe that would carry out similar attacks in order to wipe Israel off the map.

“This war is justified right to the end,” says Rony Sfadg, who managed to keep his wife and four children in a safe room in the Kisufim Kibbutz just 1km from the Gaza border, as Hamas burned and killed 17 of his neighbours.

“This can never happen again. You have to understand, the whole of Gaza is Hamas.”

On Wednesday, I met Yossi Beilin, a veteran Israeli negotiator who initiated the back-channels that started the Oslo Process, at his home in Tel Aviv.

Long regarded as a pragmatist who came close to forging a peace deal, he says the outside world should not underestimate the sense of trauma Israelis still feel over 7 October.

“Something awful happened to us,” he says.

“We cannot just say, okay, now let us talk with the other side and have a ceasefire.

“The consensus is, not to eliminate Hamas, because that is impossible and so many people support Hamas, but to prevent this group of villains, of rapists – there are no words to describe their cruelty – to prevent them from ever governing Gaza.”

However, he says the two-state solution can be revived and could deliver a deal within a year.

“We know all the solutions,” he says.

“We know the solution for the refugees, we know more or less where the border will be, if you take our Geneva Initiative of 2003 [a draft permanent settlement agreement based on previous negotiations], you have a full solution with 500 pages of very boring annexes on every issue from water to whatever, and you have the Clinton parameters of the [Camp David talks of] 2000 which will be the general ideas for a solution. So we don’t have to start from scratch.”

He adds: “The question is whether on both sides you are going to have people who are committed to the two-state solution, rather than asking for excuses why not to do it, and whether they are ready to risk their lives, knowing what happened to some of the peacemakers in the last generation.”