the struggle to build peace

The signing of the Good Friday Agreement on 10 April, 1998 was rightly seen as a momentous moment in this island’s history, a moment when irreconcilable differences were reconciled, when generations of enmity were overcome, by a deal which offered something to everyone.

It was a triumph of diplomacy, a gigantic effort underpinned by heroic exertions by the parties in Northern Ireland, and by the Irish, British and American governments.

As it turned out, that was the easy bit.

As has been shown over the past few days, as we delved through newly released government documents, the implementation of the agreement was even more tortuous than its negotiation. And, bad and all as things seemed on the surface, they were much worse behind the scenes.

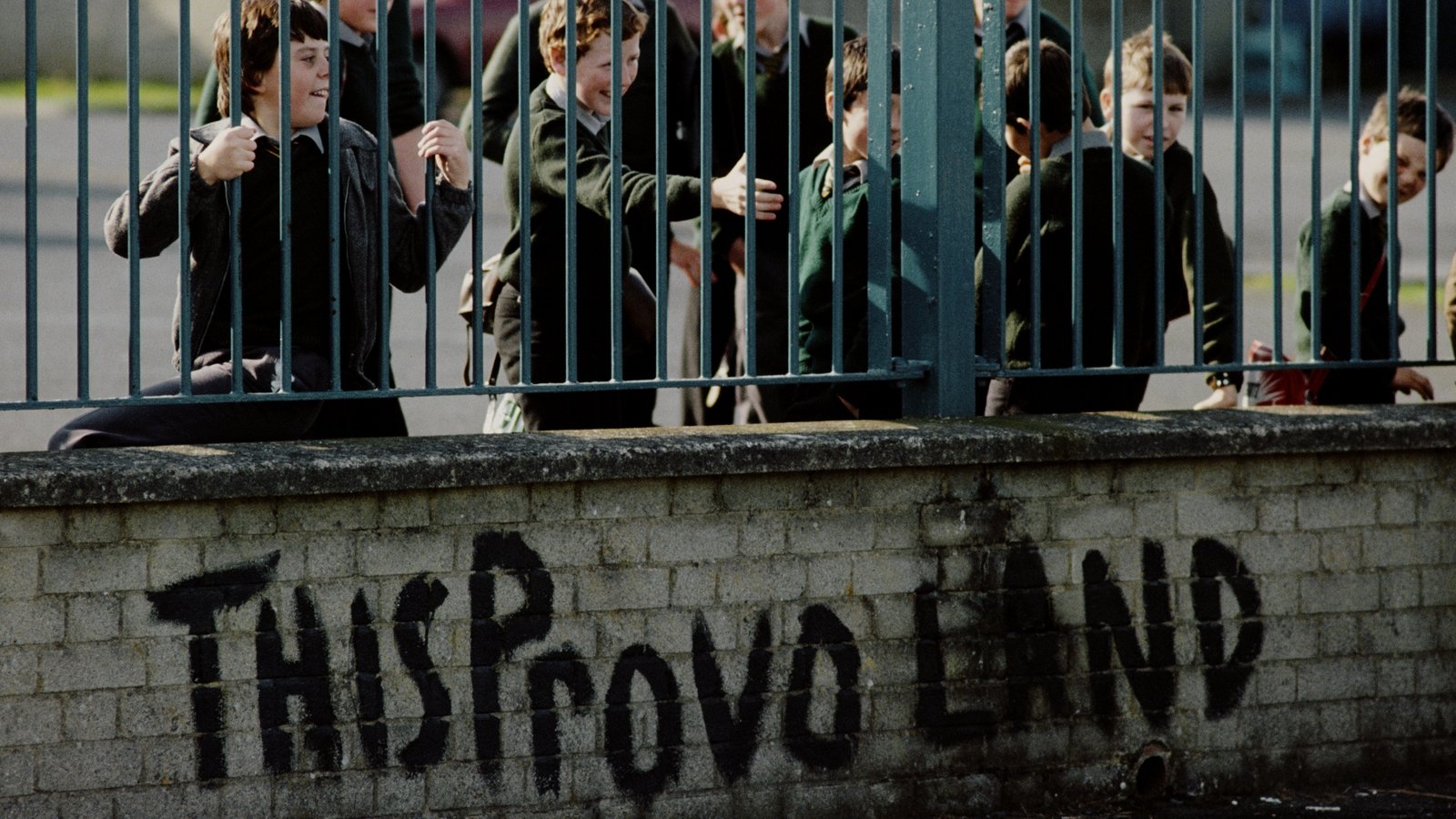

The agreement was negotiated, of course, in the shadow of violence. Just how large that shadow loomed is revealed in the documents, as is the very real fear that the unionist community would reject the deal in the subsequent referendum – particularly if certain people were to show up asking for their vote.

Northern secretary Mo Mowlam was one of the key figures in reaching the deal, but quickly fell out of favour with 10 Downing Street. As the Irish Ambassador in London, Ted Barrington, put it, Mowlam, with her “unorthodox manner and indiscreet talk around town about the Prime Minister and Cabinet colleagues, was an easy target… [her] competence was increasingly questioned…[her] role in the peace process had been eclipsed by Number 10 and… [she] had grown disenchanted with Blair and, fatally, did not conceal it”. [2022/48/616]

Her replacement was Peter Mandelson, a man with a reputation as a political genius – which, given he had to resign over ethical violations not once but twice, may be a bit undeserved.

The documents don’t do much to embellish his reputation – take for instance his forecast in July 2001, shortly after his second resignation, that Ken Clarke would defeat Iain Duncan Smith in the Conservative Party leadership election that was under way at the time.

Clarke was lazy, he admitted, but he was effective (“a little bit of Ken Clarke goes a long way”) and would pose more of a threat to Labour than Duncan Smith would. Mandelson said the Conservative grassroots, while “awful people”, liked to win, and would therefore pick Clarke. [2023/155/6]

Mandelson was wrong about that, and subsequent leadership choices by the Tory membership suggests they still prefer ideological purity to actually winning elections.

After Mandelson’s departure, the governments attempted to push the process on with increasingly inventive proposals, including a suggested “collective act of reconciliation”, which would involve British Army and RUC weapons being decommissioned alongside those of paramilitary organisations. Chief Constable Ronnie Flanagan was not impressed.

The IRA did re-engage with the Independent International Commission on Decommissioning in March 2001, but by the following June, the members of the Commission were becoming increasingly frustrated. General John de Chastelain, head of the commission, made it clear that “they were no nearer decommissioning than they had been in March”.

He and his colleagues wanted to be allowed to resign, though they were prepared to be on call for a further six months, “on the understanding that they would only have to return to Northern Ireland as and when there was specific work to be done to negotiate modalities and verify decommissioning”. As de Chastalain told a government official, while they didn’t want to walk away from their responsibilities, “they did have personal lives they needed to get on with”. However, the Commission did end up with work to do – that August the IRA agreed on a method of decommissioning, and the process was actually completed in September 2005. [2023/155/6]

Still, it is important to remember that things could have been so much worse. Another newly released document, this time from way back in 1975, considered what might happen if the British suddenly decided to leave the North. The prospects, for everyone living on this island, were daunting.

And, as always, there are other stories too, including sex toys, Francois Mitterrand, and Chris De Burgh’s private plane. Those are three separate stories, by the way, not in any way related to each other!

Where possible, we’ve given the reference numbers for the files containing the documents we’ve quoted. All of those files – along with plenty more! – are available to the public in the National Archives in Dublin when they reopen in the New Year.

By David McCullagh and Shane McElhatton