Shadowy world of intelligence and the ‘Dirty War’

When General Sir Frank Kitson died in January aged 97, the Telegraph newspaper in London described him as “one of the most capable and controversial soldiers of his generation”.

“His expertise in counter-insurgency operations was probably unrivalled,” it wrote, noting that he had received a CBE in the British honours system for service in Northern Ireland in the 1970s.

The reaction in some quarters of Northern Ireland was markedly different.

“There’ll be no sadness in these parts at his passing,” said a representative of those shot dead by British soldiers in Derry on Bloody Sunday in January 1972.

The Kitson counter-insurgency handbook had been honed in Kenya and Malay.

Some believe it was also deployed on the streets of Belfast and beyond.

They suggest loyalist paramilitary gangs were encouraged to target Catholics, nationalists and republicans and that British soldiers had been allowed to operate as they saw fit.

It may have been at its height in the 1970s but its implications continue to this day.

Earlier this month, four former soldiers who operated in a shadowy unit, the Military Reaction Force, were told they were to be charged in connection with the shootings of unarmed civilians in Belfast in May 1972.

One of them will face a charge of murder. He and three others will face counts of attempted murder.

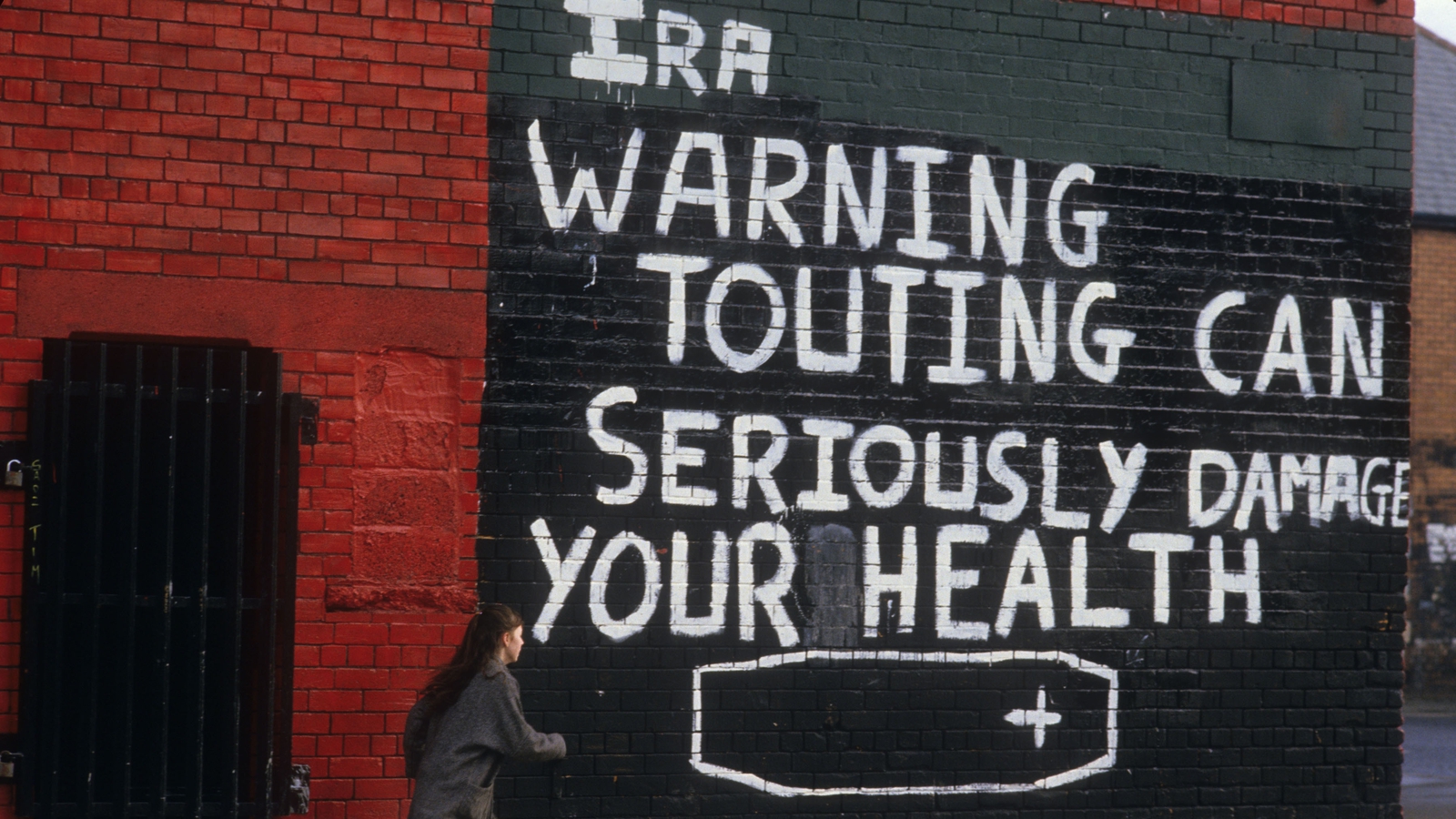

The world of informers, intelligence, counter-insurgency and secrecy, how lives were weighed in the balance and sometimes sacrificed for perceived advantage, saw the 30 years of the Troubles given another name.

It was dubbed the ‘Dirty War’.

Over the years there have been innumerable reports into some of the most controversial incidents.

Former British police officer John Stevens carried out three substantial reports into allegations of collusion between loyalists and the security forces including in the 1989 murder of Belfast solicitor Pat Finucane.

In a summary document he published in 2003, Mr Stevens said his investigations had found evidence of collusion and that he had been obstructed in trying to bring the truth to light.

Documents had been withheld, witnesses had been uncooperative, a top loyalist had been tipped off about an impending arrest and the office of his investigation team inside an RUC station had been deliberately set alight.

Investigations by Northern Ireland’s Police Ombudsman have also found evidence of collusive behaviour by police officers.

It includes the failure to warn targets of threats to their lives, the failure to exploit investigative opportunities, the failure to disseminate intelligence to detectives investigating murders and the turning of a “blind eye” to the activities of their informers.

Some killings seemed so incredulous that they prompted public inquiries.

The murder of Loyalist Volunteer Force leader Billy Wright in December 1997 was one such case.

It was carried out inside the Maze Prison, once considered the most secure in Europe.

A notorious and feared paramilitary figure vehemently opposed to the emerging peace process, Wright was gunned down in a prison van by three INLA prisoners who were on an adjoining wing of the same detention block.

They had cut a hole in the prison fence, scaled the single-storey building, run across the flat roof, dropped into the yard at the loyalist end and shot Wright with a handgun that had been smuggled into the jail.

The inquiry found failings but not collusion.

The focus of the subterfuge was not always on what happened in Northern Ireland.

In 2005, then Irish minister for justice Michael McDowell established a tribunal to investigate allegations of garda collusion in the murder of two senior RUC officers in south Armagh.

Chief Superintendent Harry Breen and Superintendent Robert Buchanan were shot dead on 20 March 1989 outside the village of Jonesborough as they returned from a meeting in Dundalk Garda Station.

The inquiry team heard from a host of witnesses including an informer. It also secured an account of the shooting from members of the IRA involved.

The inquiry’s main finding was, that on the balance of probabilities, information leaked from inside the garda station had facilitated the attack.

The days of agent handlers and intelligence, of informers and bodies found on isolated border roads feels largely like a history lesson from a different era.

However, the Troubles have a long tail and its secrets tend to emerge decades later.

Just this week in a Belfast court, a coroner halted an inquest into a Troubles murder because of requests by the British state that information it had provided be withheld on the grounds of national security.

GAA official Seán Brown had been locking up his local GAA club when he was abducted and shot by loyalist gunmen in Bellaghy, Co Derry in 1997.

The police, Ministry of Defence and British Security Services all applied for intelligence information they held about the killing to be redacted.

One folder had 56 pages in it, every single word was blacked out.

One snippet of information the family was given was that 25 people had been linked by intelligence to the murder, among them several people who had been working as informers.

Mr Justice Kinney said without access to the intelligence material a coroner’s inquest would be “seriously compromised” and a public inquiry was the only avenue that could consider the secret documents in closed session.

He has written to Northern Ireland Secretary Chris Heaton-Harris requesting one.

The Brown family’s experience exposes the continued challenges thrown up by the Dirty War.

A family seeking answers about why their loved one was murdered finds themselves frustrated by the requirement to protect informers and their handlers.

It was best summed up by the remarks of Mr Justice McKinney as he complimented the Browns on their conduct during the inquest.

He said: “I want to say to you that, from all the information placed before me, Seán Brown was an entirely innocent man who was the subject of a planned execution by LVF gunmen. His murder was senseless.

“I know that one of the questions that perplexes you as a family is why he was murdered.

“I cannot answer that question. I can say that nothing I have seen during this process to date provides a satisfactory answer to that question.

“And everything I have seen simply confirms what I was told about Seán at the start of the inquest.

“He was a man who was at the heart of his family and his community. He was a man of whom his family was justifiably proud.

“He was the kind of person our society needs, and his loss is truly felt in that wider sense.”

It was a senseless murder which, because of the shadowy world of intrigue and intelligence, remains completely unexplained.