Pub raid heightens tensions amid 1924 army mutiny

The Free State government thought its offer of terms to the Army mutineers had saved the day – until their own soldiers kicked in the doors of Devlin’s pub.

The raid

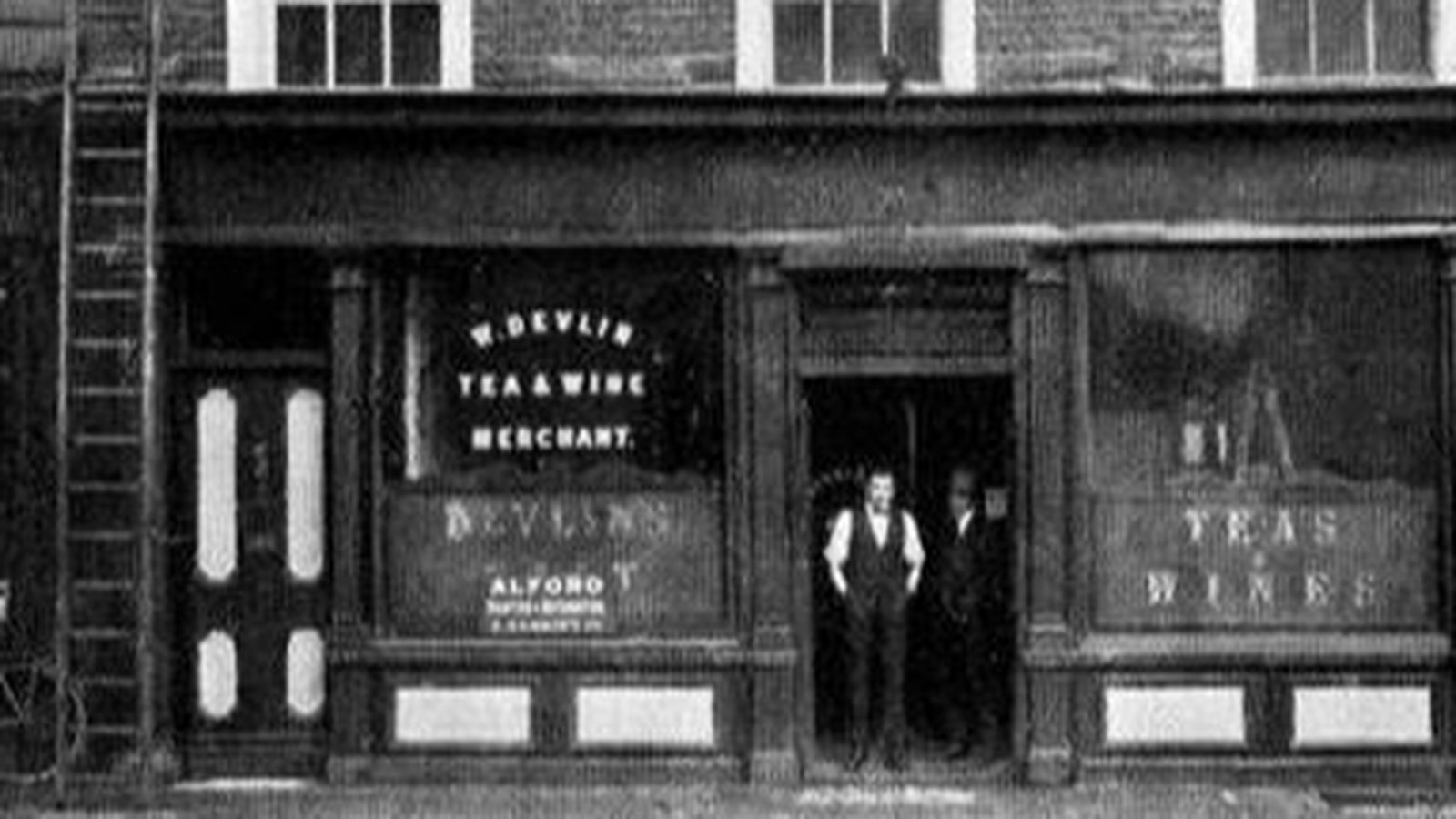

Even as the terms to the mutineers were being drawn up, word was filtering in to the Army high command that officers involved in the mutiny were meeting over several nights in Devlin’s Public House on Parnell Street, a former IRA hideout from the War of Independence.

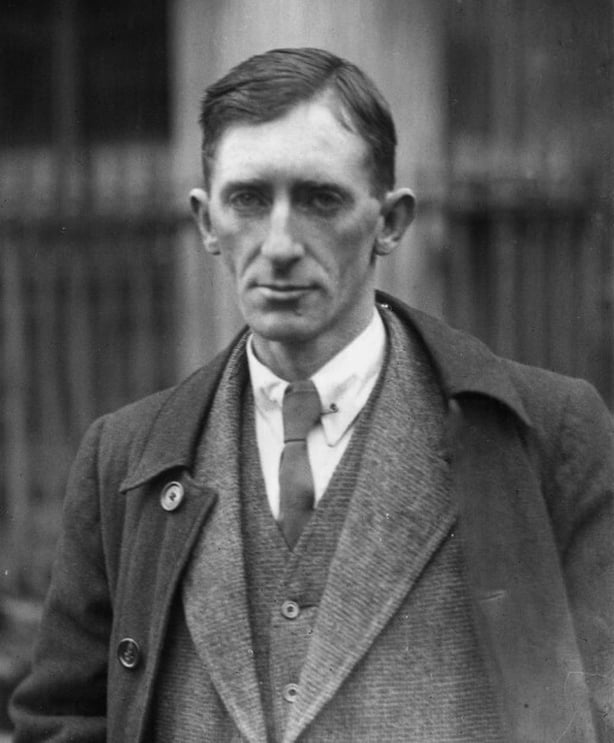

On the night of the 18 March – the very same day Richard Mulcahy as Minister of Defence had sent the Army Council the terms and deadline for the mutineers to surrender – he ordered soldiers surrounding Devlin’s pub to raid it and arrest every officer found on the premises.

He acted in conjunction with the Army Adjutant-General Gearóid O’Sullivan, the officer in charge of army discipline.

Left entirely out of the picture by General Mulcahy that night were: President Cosgrave, the entire Executive Council and Eoin O’Duffy, the new General Officer Commanding the Defence Forces.

The public and the press might have seen the raid as a nick-of-time strike against men bent on leading an armed insurrection, but the Executive Council saw it very differently.

In their view, the timing could not have been worse, with the city a tinderbox, while the mutineers’ response to the government’s terms was awaited.

Had the mutineers decided to make a stand, and make a fight of it, how would officers and men of the Army, who had up to then remained at their posts, have responded to deaths and injuries on either side?

Would it have been a call to arms to those in the ranks still undecided about the mutineers’ cause?

How many would see the raid as government treachery – when the government had in fact been literally the last people to know about it?

‘Set the heather on fire’

The next day the government wielded the axe.

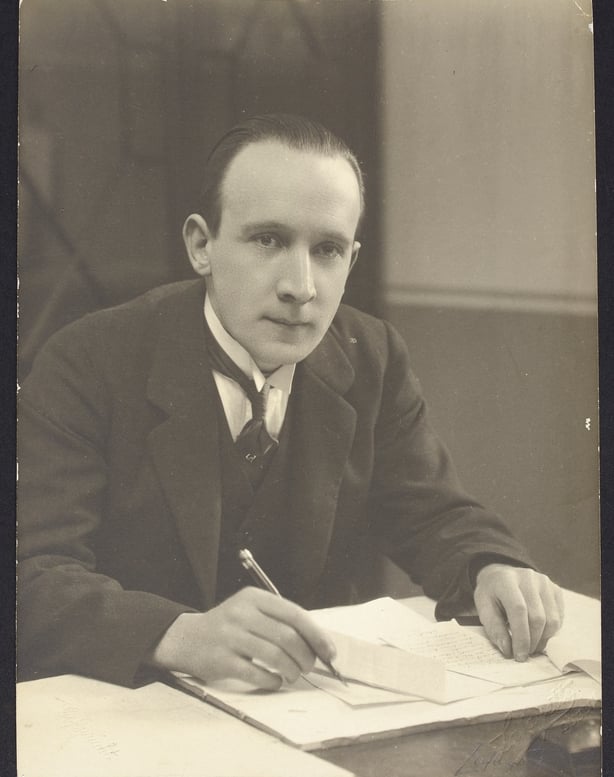

The Minister for Home Affairs Kevin O’Higgins told the Dáil that the government believed that the raid cut across government policy and intent and it had jeopardised efforts to resolve an extremely dangerous and delicate situation by setting off a new conflict.

This was an action “calculated to have, possibly, grave reactions within the Army and throughout the country, calculated perhaps to set the heather on fire, the heather we have been so assiduously attempting to quench and damp down”.

Therefore, he said, the government had sought the resignations of the entire Army Council, the Chief of Staff General Sean MacMahon, Lieutenant-Generals Adjutant-General Gearóid O’Sullivan and Quartermaster General Sean O’Murthuile from their army posts, but not from their commissions (their certification as officers).

Generals O’Sullivan and O’Murthuile resigned immediately. As a mark of their disgust at how they were being treated, they also resigned their commissions.

General MacMahon refused to resign, and was removed from both his post and his commission.

The government did not stop there. They also demanded the resignation of General Mulcahy from his role as Minister for Defence.

He got out ahead by resigning in protest at the termination of the careers of the three generals.

The centre held; the officers accepted their fate. Both Generals McMahon and Mulcahy explicitly told their subordinates that there should be no Army reaction against the government’s decisions.

A few days later, O’Higgins and Mulcahy squared up to each other in the Dáil chamber.

Neither held back.

O’Higgins said the wave of dismissals was not just for the raid, but in response to a concern that had been growing among members of the Executive Council; that within the Army, factions, organisations and societies, secret and semi-secret, were building and circling each other.

In the peacetime Army that was now being created, they had to be rooted out.

The unsanctioned raid on Devlin’s pub was seen by the government, not as a military operation, but a case of one faction striking against another.

‘Condoning mutiny’

Richard Mulcahy accused the Executive Council of condoning and fostering mutiny in the Army by allowing the illegally-armed mutineers to openly meet in the city, mocking government authority.

He presented himself as the sole defender of the law of the land: “Refusing to put the law into effect is condoning mutiny and fostering it, and my resignation was tendered because I could not stand over that.”

He claimed that he had not consulted the incoming officer commanding the Defence Forces, General O’Duffy, because his powers had not yet been legally defined.

He said this meant that on the night of 18 March, General O’Duffy was not officially in charge.

This was feeble. Even if General O’Duffy’s powers were not yet fully laid down in law, he was the government’s new man at the top of the Army, sent in expressly to mark a new beginning, and Mulcahy knew it.

Joe McGrath accused him of ordering the raid as a final act of defiance before O’Duffy’s powers were made official.

Labour Leader Thomas Johnson told him that if he accepted responsibility for making the offer of terms to the mutineers, he should not have sanctioned the raid.

Trust dies slowly; the last straw

Mulcahy may have claimed that he was acting to the letter of the law, but for a soldier/politician who had rendered such great service to the new state, his judgement in ordering the raid just after agreeing the terms of surrender to the mutineers, was shocking.

In the end, his protestations were in vain. His former colleagues in government simply did not trust him anymore.

That trust had died in stages.

Back in September 1922, as it became obvious the Civil War could not be contained or curtailed without a massive fight, Mulcahy had sat around the Executive Council table and solemnly agreed with his colleagues that there would be no unofficial back-channel meetings with leaders of the anti-Treaty forces.

Mulcahy left that meeting – and went straight into an unofficial back-channel meeting with Eamon de Valera.

Other Ministers never trusted him after that.

Then, six months later, when senior Kerry Command officers were facing calls for their investigation and prosecution for atrocities and physical assaults on civilians and anti-Treaty prisoners, Mulcahy shielded them so blatantly that O’Higgins nearly resigned from the government.

O’Higgins regarded Mulcahy’s stonewalling and backstairs dealings as revealing an attitude among the military men that the War of Independence veterans in the Free State Army could write their own regulations, nod-and-wink rules for those ‘in the know’, that elected civilians of whatever seniority in government could never challenge.

O’Higgins recalled the Executive Council meeting in February 1923 when Mulcahy had ‘blandly’ denied any idea that the IRB was reforming and assembling inside the Army.

The raid on Devlin’s was the last straw.

Never waste a crisis

On the principle that no crisis should ever be wasted, the government cleaned house.

The dismissed officers were replaced within 24 hours. Mulcahy’s brief was taken by the President himself.

The next step was to defuse the crisis, without creating a new one. And if that took a strong dose of look-the-other-way pragmatism by the State, so be it.

The deadline set for the mutineers to surrender themselves and the stolen weapons was extended to Saturday 22 March.

The day before, the officers arrested in Devlin’s were released on condition that they would make the required formal submission to the authority of the State.

The new deadline came and went. Stolen weapons and ammunition began to trickle back, using Joe McGrath as the go-between.

In the end, the officers never surrendered themselves for open arrest and formal declarations of loyalty.

They simply resigned, and walked away from their army careers, into the harsh uncertainties of civilian life, but without the stigma of dismissal that hung over the men who had taken action against them.

On 26 March Kevin O’Higgins proposed to the Dáil that the resignations be accepted and that there be no question of arrest or court-martial.

He reminded the Dáil that during and after the Civil War, the government spared from charges of treason thousands of anti-Treaty IRA prisoners who, if convicted, would have been imprisoned for 15 to 20 years:

“Why? Not on merit, but because it was not considered politic in the interests of the state that these men be tried and sentenced for treason.

It is all opportunism if you wish, but there needs to be opportunism in the handling of national affairs and very delicate situations.” O’Higgins said.

The clear implication was that there were times when the government had to stay its hand, in the greater cause of a return to peace.

With the prisons still not fully emptied of anti-Treaty prisoners, the government was already steeling itself for the release to their families of the remains of the 81 men executed during the Civil War.

That would be a traumatic and angry experience.

The notion that at the same time the State would start to fill up the prisons again, this time with men who had served the Free State in its hour of greatest danger, to be guarded by men they had once commanded, was too much to bear.

The supreme irony was, as Mulcahy pointed out after his resignation, that the reaction of the dismissed senior officers to the ending of their military careers refuted any idea that the officer corps held itself above the rules of a parliamentary democracy; when they were dismissed, or resigned, the officers obeyed their elected civilian superiors, they left their posts after ordering their angry subordinates to stay their hand.

So, was it all a hysterical misunderstanding, an overreaction by the government?

The danger posed by the existence of the IRB in the Army was not so much what it was at that moment, but what it could have grown into, if left unchallenged.

No government could allow a secret oath-bound society, approved and protected by the High Command, claiming an exclusive right to judge how the elected government of the day was guarding the Republican flame, to exist inside the Army’s officer corps.

That was how military coups began.

Legacy.

There needed to be some legacy from the Army crisis, that would leave the State certain of its soldiers’ loyalty.

On 3 April, the Army Inquiry Committee was established by President Cosgrave.

Its mandate was: “To enquire into…. the facts and matters which have caused or led up to the indiscipline and mutinous or insubordinate conduct lately manifested in the National Army.”

Over two months, the Committee interviewed 27 witnesses at over 40 meetings.

On 7 June, the Committee submitted its findings to President Cosgrave.

‘A disastrous error of judgement’

The findings were unanimous. They were blunt and spared neither mutineers nor the men against whom they mutinied.

The findings:

– The Irish Republican Army Organisation was in existence since before the Civil War.

– The IRAO did not see the Army as non-political.

– The IRAO believed that the Army should impose its views on the civil government.

– The IRAO believed the Army should be officered by men like them.

– The Inquiry found that the IRAO objectives and methods were wholly incompatible with discipline and obedience.

– However, their activities were intensified by the revival of the IRB in the Army, with the encouragement of certain members of the Army Council, and the Minister for Defence never told the Executive Council what was going on.

– There was no confidence or intercourse between the two groups of officers.

– The revival of the IRB within the Army was “a disastrous error of judgement” by the High Command.

– It accentuated a mutiny that might never have happened, or could have been more firmly suppressed if those in command had not weakened their own authority by being seen to act in the interest of a hostile secret society.

– There was no evidence of appointments or promotions being made by reason of membership of the IRB, but the mere suspicion of influence corruptly exercised by the IRB undermined confidence in the impartiality of the Army Council and higher commands.

– That suspicion could not be tolerated in the Army.

The Inquiry Committee recommendation was that there be a complete ban on such societies in the Army, and that in future, all officers would have to formally declare they were not members of any such bodies, in the same way recruits to the Civic Guard/Garda Siochána already did.

This was in many ways the end of the Revolutionary era.

There were strong echoes of Michael Collins’ insistence two years earlier, that the Free State’s new police force would be a clean break with the past, made up of men selected, trained and sworn-in to serve a peacetime role.

In the same way, the government wanted the peacetime Army to be a break with the past.

The Army Mutiny had put the country on the world’s front pages again, for all the wrong reasons.

New York Times readers saw the front-page story of the mutiny alongside reports of coups in Honduras or El Salvador or the latest outrage in revolutionary Germany.

The nightmare returned that had haunted the government during the Civil War – that in an era of chaos and conflict across the globe, the Free State would be dismissed as just another small nation engulfed in a doom cycle of self-reinforcing chaos.

All the hard graft of winning and ending the Civil War, the battle for acceptance at the League of Nations, the beginning of an assertion of identity inside the British Empire to lay the groundwork for full independence, the slog of building financial credibility at home and abroad – all could have been in vain.

The government chose to ‘win’ the standoff of the Army Mutiny by binding the wounds, learning the lessons and moving on.

This is Part Two in this story, to read Part One, click here: Army mutiny of 1924 threatened to ignite a new civil war.

Read more: Hunger strike: The last act of the Civil War

Death on a bare mountain: The end of the Civil War

‘It would be a great pity if Collins were killed’