Protests a ‘daily tirade of abuse and intimidation’

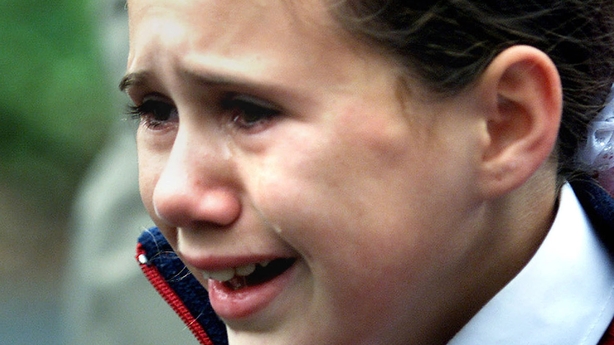

Few episodes illustrated the continuing tensions in post-Good Friday Agreement Northern Ireland more than the loyalist protest against the pupils of Holy Cross primary school in Ardoyne in Belfast.

The children and their parents faced a “daily tirade of abuse and intimidation” on their way to and from school each weekday for months on end.

As a Department of Foreign Affairs official noted, “the trouble started on 20 June 2001… when a man was attacked as he collected his child from school and a standoff developed between the children’s parents and loyalist residents”.

According to nationalists, the man was targeted because he objected to loyalist paramilitary flags being put up on the Ardoyne Road.

Whatever the immediate cause, the result was a daily protest along the route to school by residents of the loyalist Glenbryn Estate, which continued until the summer break, and resumed at the start of the new school term.

The official added: “The hate-filled aggression the loyalist protesters showed to the primary school girls and their families has disturbed, dismayed and angered people throughout Northern Ireland and in the wider world beyond.”

The protest continued for 12 weeks that autumn, at an estimated security cost of £3m.

While the dispute began over paramilitary flags, the loyalist community claimed they were protesting over the wider issue of attacks on them from the nationalist community. They demanded greater safety and security measures in the Ardoyne area, including road ramps, CCTV, community policing and a new forum for dialogue between the communities.

Nationalists were greatly encouraged by a visit to the local Holy Cross Monastery by president Mary McAleese on 9 November. In advance of the visit, northern secretary John Reid suggested “it might be wise if she was to signal a willingness to also meet the Glenbryn residents (even if they chose not to take up the offer)”. Brian Cowen, the minister for foreign affairs, “noted” the point, though it’s not clear if it was acted upon.

The president’s visit was seen as “a major morale boost for the children and their parents”, according to local Sinn Féin councillor Eoin Ó Broin (now a TD), but there was criticism that government ministers hadn’t followed her lead. Ó Broin asked if education minister Michael Woods could visit, perhaps joining his Northern counterpart Martin McGuinness to “walk up the Ardoyne Road with the children and their parents”.

One of the parents asked Irish officials in Belfast if the minister or the taoiseach could come to “demonstrate solidarity with the children… He claimed that parents would welcome a high-level visit even if it led to the predictable outcry from the loyalist protesters and Unionist politicians”.

Meanwhile, on the other side of the fence, loyalists were convinced that they were the victims. Davy Mahood, local representative of the Ulster Democratic Party (which was linked to the paramilitary group the UDA), claimed that the police were trying to gain favour with nationalists by “cracking Protestant skulls”. He was particularly critical of Chief Constable Ronnie Flanagan and Assistant Chief Constable Alan McQuillan, “both local Protestant boys who showed no sympathy for Loyalists”.

At the end of November, an intervention by First Minister David Trimble and Deputy First Minister Mark Durkan finally secured agreement, with promises to meet the Glenbryn residents’ demand – though the protestors said they were only “suspending” their action, not ending it.

Sure enough, trouble re-erupted at Holy Cross in January 2002, with “hand-to-hand combat” between loyalists and republicans after a group of men invaded the school car park and damaged vehicles.

Sinn Féin political representatives made a big effort to keep a lid on nationalist emotions. At “extremely angry” meetings with parents, MLA Gerry Kelly and local councillor Martin Meehan stressed the need for “a calm and measured response”, rather than “walking into a loyalist trap by breaking the ceasefire”.

Thankfully, the dispute did eventually fade away, and children were free once again to walk to school in peace.

By David McCullagh and Shane McElhatton

[Based on documents in 2022/48/610; 2022/48/758; 2022/48/759; and 2023/54/66]