Perilous charm offensive ahead for Von der Leyen

Despite the far right and hard right gains in the European elections, EU leaders have this week steered the European project away from the shoals with their handling of the top jobs.

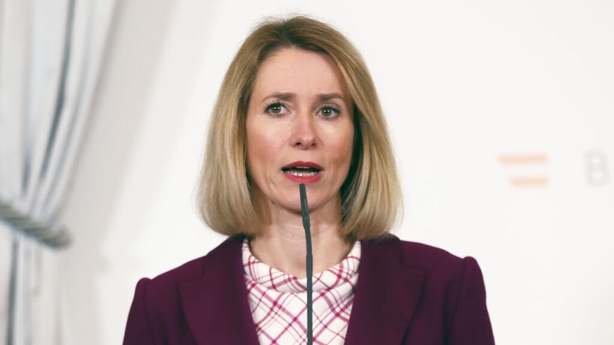

Leaders from the centre-right, centre-left and the liberals managed to close the deal on the candidates ahead of the summit: Ursula von der Leyen for a second term as Commission president; former Portuguese prime minister António Costa as president of the European Council; and Estonian prime minister Kaja Kallas as the EU’s foreign policy chief.

Nerves were also steadied on Ukraine: in the interregnum between the elections and Hungary taking over the rotating presidency of the EU, member states adopted the 14th sanctions package against Russia and formally opened accession negotiations with Ukraine and Moldova, while on Thursday EU leaders signed a security agreement with President Volodymyr Zelensky.

It is by no means business as usual, however.

Despite Hungarian diplomats in Brussels promising a pragmatic approach to the presidency, prime minister Viktor Orban can still slow down progress on EU legislation, while the impact of a bigger far-right footprint in the European Parliament has yet to be felt.

The prospect of a far-right government in France – the traditional powerhouse of the European project – has left many in the EU very nervous.

“There are straws in the wind in terms of the growth of certain [far-right] parties and movements which we cannot ignore,” Tánaiste Micheál Martin told reporters in Luxembourg on Monday, “and it certainly will be a challenging time ahead for Europe in respect of the European Union ideal.”

Keeping Italian prime minister Giorgia Meloni on the right side of that ideal has been the objective of pro-European leaders in recent months.

The leader of the hard right Fratelli d’Italia (Brothers of Italy) has taken a constructive line on Ukraine and has parried the advances of Marine Le Pen of the French Rassemblement National (RN), or National Rally, who wanted to create a radical right supergroup in the Parliament.

However, Meloni was furious that she was not cut in on the top jobs deal, given that her European Conservatives and Reformists (ECR) group will emerge as the third largest in the Parliament, ahead of Emmanuel Macron’s Renew group.

Despite that, the three names – Von der Leyen, Costa and Kallas – were never really in doubt.

On 17 June, EU leaders met for an informal dinner for a first attempt. There was no agreement (the EPP made an ill-considered bid to grab half of the five year term of Council president) but the three names there at the start of the dinner were there at the end.

That the deal was pre-cooked behind closed doors by six male negotiators was not, diplomats acknowledged, a good look.

But the negotiators were Greek prime minister Kyriakos Mitsotakis and Poland’s Donald Tusk, German Chancellor Olaf Scholz and Spanish prime minister Pedro Sanchez, Dutch prime minister Mark Rutte and French president Emmanuel Macron, and they represented the three political groups (EPP, Socialists and Renew), which have a clear majority on the European Council.

The EU Treaties state that a qualified majority of the 27 leaders is all that is required to nominate the Commission president.

The summit may still have been overshadowed by Macron’s high-risk gamble to dissolve the National Assembly and trigger legislative elections after his party was trounced by the far-right National Rally in the European poll.

Even then there appeared little sense of panic that a founding member of the EU, and usually seen as the joint engine of European integration with Germany, could soon be governed by the far-right.

“[Macron’s] actual and potential setbacks in France are not, in other words, a threat to the EU as such, even though they have caused and will doubtless continue to cause the Union a great deal of turbulence,” wrote veteran observer Peter Ludlow in a paper for Eurocomment.

For the moment, diplomats are keeping their counsel on the basis that the results of the election are not yet known. Even if he loses badly, Macron could still hold on to the levers of foreign and security policy as president, even in a co-habitation with the RN.

For those speculating what that co-habitation might look like, observers point to Meloni as an example of how a party with far-right roots can surprise the outside world by acting in a constructive and pragmatic way on the European stage.

Despite the post-fascist provenance of her party, Meloni has been seen as working effectively at EU level with centrists,

However, still wincing from her exclusion from the top jobs process, Meloni abstained on von der Leyen, despite the German Commission president wooing Meloni’s affections for months. She also voted against Kallas and Costa.

Some diplomats believe Meloni has been weakened by her performance at the European Council.

She had hoped that she could get the support of Orban and the soft-eurosceptic Czech prime minister Petr Fiala at the very least in order to get some recognition of the ECR’s bigger presence in the European Parliament.

This despite her sustained flirtation with von der Leyen and the centrist bloc.

“She’s the leader of the third biggest economy in Europe, and she’s a serious politician from a serious country,” says one EU diplomat.

“But this has weakened her in the eyes of the others, because they’ve isolated her. At the European Council it is pure power politics and it’s all about the numbers. She didn’t have the numbers and everyone around the table knew she didn’t have the numbers.”

Meloni will still be a force to be reckoned with. She could insist that the ECR does not throw von der Leyen a lifeline when the Parliament votes on her nomination in July.

The working majority that has been constructed since the elections – the EPP, Renew and S&D – looks perilously thin for von der Leyen. They currently have some 398 MEPs and she needs a majority of 361. Taking into account the dissension rate of around ten percent, Von der Leyen needs every vote she can get.

That’s why there’s clear unease in Fine Gael that, at a time when Ireland is trying tosell Michael McGrath as a candidate for a high-profile economic portfolio in the next Commission, four Fianna Fáil MEPs are threatening to vote against von der Leyen.

“Four votes matter on this,” said a Government source. “It’s as if a party negotiating a coalition government said, we’re going to vote against you as prime minister, but give us the finance ministry.”

What makes it more delicate is that Harris cannot be seen to be putting pressure on Fianna Fáil MEPs.

Any approaches by Micheál Martin to the MEPs appear, so far, to have been rebuffed, so strong is the animus towards von der Leyen, and so public the declarations by the MEPs that they would not support her nomination in the Strasbourg vote.

“It’s about her unconditional support for Israel,” says one of the MEPs. “The fact that she never made any effort around banning products from the occupied territories, she never spoke out even in advance of the massacre on 7 October about killings in the West Bank. She never criticised Israeli brutality.”

Supporters of von der Leyen within the Irish political sphere say she has been unfairly demonised and that, despite her initial missteps, has worked hard on securing humanitarian aid for Gaza and ensuring that EU funding for the Palestinian relief agency UNRWA continued when many countries in the West were suspending it after allegations that UNRWA staff had participated in the October 7 attacks.

Yet, the coalition’s linking of the issue with Ireland’s prospects of getting a strong economic portfolio for McGrath has also rankled MEPs.

One MEP pointed out – with surprising bitterness – that Ireland had a very high-profile portfolio when Phil Hogan was the EU’s trade commissioner, yet that didn’t stop Fine Gael and Fianna Fáil “skinning him from chin to toe” over the Covid-19 golf controversy.

Some senior figures within the European Commission believe that the Fianna Fáil MEPs could do real damage to Ireland’s prospects, and they also question whether Ireland was wise to go so early with the McGrath nomination.

One EU diplomat says there is “no harm” in getting the name out early and creating a narrative. “If I think of the financial services portfolio, I think of Ireland and Austria and their two candidates at this point. So that frame has been set,” says the diplomat.

The Taoiseach believes getting McGrath’s name out there, and promoting his credentials are important.

It’s understood Harris believes Fine Gael’s position within the EPP – von der Leyen’s party – will be leveraged to the hilt (Harris can argue that as one of the EPP leaders around the European Council table, he played his part in getting von der Leyen the nomination).

Harris spoke to von der Leyen by phone last Saturday about McGrath’s candidacy. It’s understood she asked a lot of questions about his experience; she was also keenly aware of the intention of Fianna Fáil MEPs to vote against her.

After her nomination on Thursday night, von der Leyen acknowledged that she had a lot of outreach to do, and that included talking to national delegations in the Parliament (although she didn’t refer to the Fianna Fáil delegation, it’s a worthy bet that that’s whom she was referring to).

“Experience shows that it is the national delegations which often take their decisions [together],” she told a news conference. “This includes, of course, individual MEPs: most of them are supportive, but for those who are critical, or who have questions, my duty is to get in contact with them and answer their questions.”

Senior Irish figures see von der Leyen as having a strong mathematical instinct where numbers are all that matter, and if that requires getting some face time with Irish MEPs to try to win them over then so be it.

Von der Leyen was elected by the Parliament in 2019 with a margin of just nine votes. The political pressures she faces are more intense today, despite widespread admiration at her handling of the Covid emergency and Russia’s invasion of Ukraine.

At the same time, a rejection by the Parliament would produce an unprecedented constitutional crisis for the EU, at a time when it can least afford it.