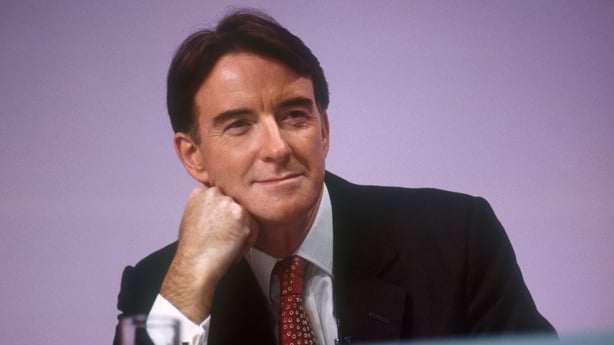

British concerns ‘Peter will get us into trouble’

Peter Mandelson came to Belfast in October 1999 with a lot to prove. A legendary political operator and close friend of Tony Blair, his previous cabinet post as trade secretary was ended the previous year by an ethics scandal after just six months.

The Irish Ambassador to London, Ted Barrington, wrote an incisive assessment of the new northern secretary, pointing out that the new job was his “big chance to show that he is more than a backroom manipulator”, and that he realised how important the peace process was, thanks to Tony Blair’s massive personal investment of time and political capital.

Nonetheless, it was open to question whether he had a long-term interest in Northern Ireland, or just saw the job as a “purgatorial” stepping stone back into mainstream politics. He had made no secret of the fact that the job he really wanted was foreign secretary – which Barrington thought was a possibility if he succeeded in the Northern Ireland Office.

Significantly, while Mandelson was perceived in political circles as being more sympathetic to unionism than to nationalism, the ambassador said he personally saw no strong evidence for this, though he would probably be more “neutral” than his predecessor, Mo Mowlam, generally seen as pro-nationalist.

Ambassador Barrington thought that under Mandelson, “things will be different from the past eighteen months or so, when it was clear that Blair had lost confidence in Mowlam’s abilities and felt that he had to take on too much of the burden himself”.

Fifteen months after marking his arrival, in February 2001 Barrington was writing Mandelson’s political obituary; a second ethical scandal had led to a second resignation.

If his initial assessment had been lukewarm, by now the ambassador was scathing. He wrote of how Mandelson “courts the media relentlessly, telephoning reporters, correspondents and editors, to charm or cajole”. He said Mandelson had assumed the issues in Northern Ireland would be quickly resolved, leaving him with “time to devote to matters which really interested him – advisor to the PM, the consolidation of the New Labour project, the preparations for the election, Britain’s relations with Germany and the Government’s European policy… But Northern Ireland was more complex and demanding than he may have imagined… and tested his abilities and resilience”.

Mandelson’s judgement had been questioned in the Labour Party and in the media when he suspended the assembly and executive in February 2000 over decommissioning; and he was “surprisingly sensitive and insecure in private” over this criticism.

His colleagues constantly discussed his personal life, and “expressed fears about further scandals. ‘Peter will get us into trouble’ was a fairly constant refrain. Some of this was undoubtedly homophobic, but his enemies had no compunction in spreading the most scandalous stories about him and his partner”.

His return to cabinet had exacerbated tensions between the warring New Labour factions – on one occasion, Barrington observed Mandelson and chancellor Gordon Brown ostentatiously ignoring each other while passing in a Westminster corridor twice in a matter of minutes – but his problem was that he had “no real friends in the party or in Cabinet”. While he had the prime minister’s support, he was untouchable; once he lost that, he was in trouble.

And, as Barrington wrote, while “he was still close to Blair… I was struck when I saw them together that the relationship was not as cosy or as equal as the media would have us believe”. A second ethical difficulty proved too much for Blair, and “when the second fall came, there was no one to speak for him, and few tears shed”.

Mandelson’s successor, John Reid, could hardly have been more of a contrast: a working-class, Catholic Scot, Reid was described by the embassy in London as “smart and personable, but a tough and self-confident operator who does not take prisoners when the political going gets rough. He is certainly more personable than Mandelson and has none of Mandelson’s supercilious or condescending manner. Nor does he have Mandelson’s metropolitan preoccupations”.

A similar assessment came from a (very) junior minister at the Northern Ireland Office, George Howarth, who told Irish officials that they would find Reid much easier to deal with: “he has a ‘roaming and inquiring mind’ and this makes him more open to other people’s views than was the case with Peter Mandelson… while one of Mandelson’s great strengths was his ‘tunnel vision’, his greatest weakness was also his ‘tunnel vision’”.

By David McCullagh and Shane McElhatton

[Based on documents in 2022/45/132; 2022/48/616, 2023/155/6, and 2023/155/22]