Army mutiny of 1924 threatens to ignite a new civil war

The soldiers crouched on the roof of Devlin’s Public House could hardly believe their ears.

Below them, in a valley between two rooftops, they had cornered 11 men, trench-coated and armed.

One of the trapped men looked over the parapet and in a parade-ground voice, one clearly used to being obeyed, yelled one word – “Surrender!”

Taken aback for a moment, the soldiers then remembered why they had climbed up on the roof in the first place. They moved forward.

The trapped men had maybe a second to decide how this would play out – gunbattle and almost certain death – or surrender and take their chances.

They surrendered.

There would be at least another act in this drama. No sense in not being around for it.

Hands in the air, the men trod slowly down the narrow staircase, until they were lined up at the bar.

From the frisking and the searching, pistols and ammunition were pulled from belts and coat pockets. The odd dropped bullet bounced and skittered across the floorboards.

A search on the roof found another pistol and three dum-dum bullets – ordinary bullets made even more vicious by having crosses gouged into the tips.

The soldiers finally got a chance to look over their bayonets into the faces of their prisoners.

They must have wondered what the hell was going on.

The Civil War had been over since the previous summer.

The captured men were not die-hard on-the-run IRA Irregulars.

The soldiers were looking into the eyes of their own superior officers.

They counted off: four colonels, four commandants, one of them the aide de camp to the president; two ex-commandants and one ex-lieutenant.

So was this how the story ended, the Army Mutiny of 1924 nipped in the bud, a dastardly and fiendish plot foiled, with a nation’s grateful thanks about to be bestowed on the men behind the raid on Devlin’s Public House?

Or had the raid been a reckless adventure that came within seconds of igniting a new civil war and collapsing the infant Free State?

Within days, the army careers of those men who ordered the raid would be over, as over as the careers of the men they arrested.

The final act of the Revolutionary era was about to play out.

Demobilisation

Since the previous summer, as the collapse of the anti-Treaty forces brought the Civil War to a close, the government knew that it could not put off for long the inevitable end to any war – demobilisation.

The Army was, relative to the size of the population, one of the biggest in the world.

It was costing the government £10 million a year, equivalent to €885m today, an astronomical sum that the new State could not bear any longer.

Demobilisation hurt.

Men who one day were ordered to risk their lives unto death, were the next day told their services were no longer required and shown the door.

The world waiting outside for them had changed; the jobs they left were filled by men who had hung back.

New jobs were scarce in an economy now having to wrench itself back to a peacetime footing.

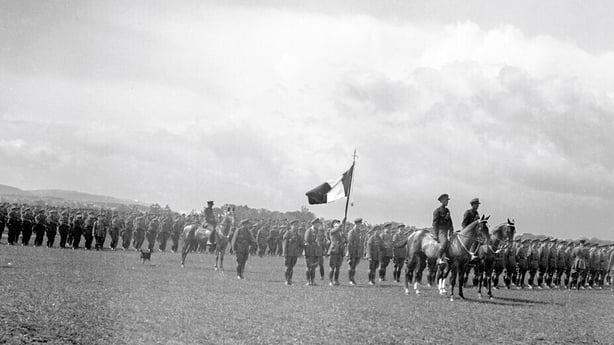

The mobilisation of the war effort by the infant Free State in 1922 had been astonishing.

An army was created almost overnight by Michael Collins and Richard Mulcahy, from the bare bones of a handful of War of Independence-era units, many of whom had chosen the Free State side mainly out of loyalty to Collins and to their own officers.

From those few thousand men, the Army ballooned in a few months to a strength of over 50,000 soldiers, most of whom were sworn in and sent straight into battle, without the most basic training.

Most armies get the time to grow and develop, building on experience and tradition to build up an ethos and a way of doing things by the book.

The Free State Army got no such time. It could only draw from its roots, from the rough-and-ready experience of war with the British, and no sooner than it had been built up, it was to be drastically drawn down.

The demobilisation undertaken by the Free State in 1924 was unique in its complexity and in the existential threat to democratic rule it posed if it went wrong.

The government was dealing with:

– An army that two years before, did not even exist.

– An army whose first task had been to turn on its former comrades.

– An army whose nucleus was held together by personal loyalties to officers and comrades.

– An army whose founders had made their reputations by running an insurgency against the British based on usurping, challenging and undermining by ambush, sabotage and subterfuge every military force, every law and every regulation put up by the former colonial power. The founders had had to instill in the soldiers of the new army obedience and respect for the exact opposite and the government had expected that change to happen overnight.

Reputations earned in the War of Independence would count for nothing and that was going to be painful.

From a strength of 50,000 men, the plan was to aim for a book strength of 17,000. That meant laying off tens of thousands of men and hundreds of officers.

Particular attention was paid to the demobilising of officers.

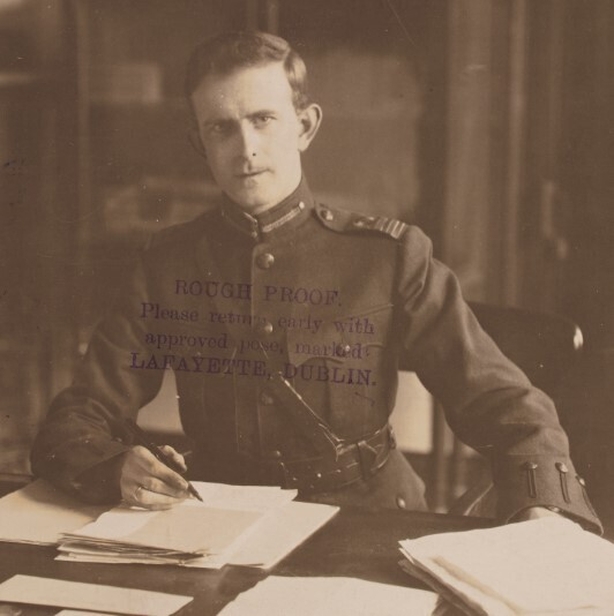

For ten days in February 1924, the Commander-in-Chief of the Army and Minister for Defence, General Richard Mulcahy, and his senior officers in the Army Council worked on the list of those officers to be offered posts – and the list of officers who would be deemed surplus to requirements.

Secret societies and an inside track

A peacetime army would need officers with a skillset that would not automatically match the one needed in the War of Independence.

To many of those officers chosen for demobilisation, it seemed that their achievements in that war were being ignored and preference given to ex-British Army officers and to men who had only become officers in the Civil War.

The summer of 1923 saw a series of frustrating and indecisive meetings between the disgruntled, soon-to-be ex-officers and the Army command.

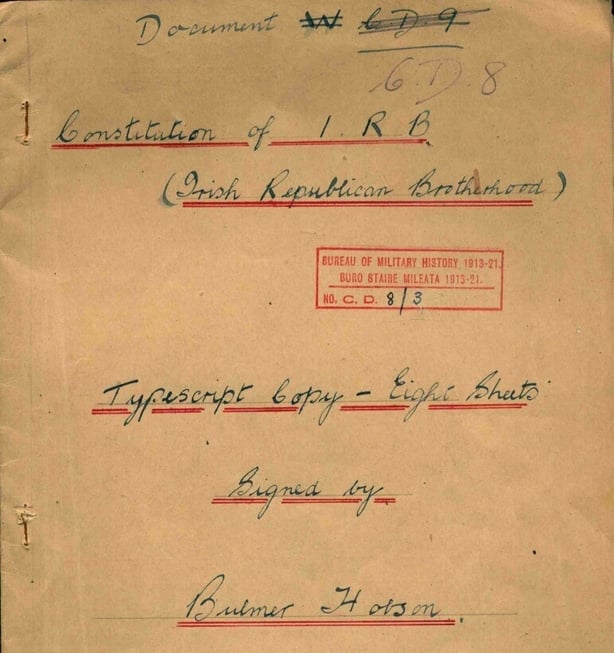

The protesting officers had become convinced that there was an inside track in the Army, based on membership of the old Irish Republican Brotherhood, a secret society founded in the 19th century, long predating the Volunteers and the IRA, and to which many of the senior army officers belonged.

The conviction grew among the protestors that jobs in the peacetime army were being assigned only to members of the IRB.

They set up their own society, claiming to be the real keepers of the republican flame, hence the name: The Irish Republican Army Organisation (IRAO).

The Army command and the Executive Council (The Cabinet) rejected the allegations of favouritism, but the fact was that the IRB had been re-established in the Army in 1923.

The justification – with scant evidence to support it – given by General Sean O’Murthuile for its re-establishment was that it was approved to pre-empt the anti-Treaty side from claiming the IRB as its own.

Generals Mulcahy and O’Murthuile had been on the original IRB Supreme Council.

Mulcahy had gone as far as discussing an early draft of a revamped IRB constitution and how a revived IRB would be organised inside the Army.

He claimed later that he saw the IRB as a force inside the Army that needed to be controlled and directed.

Yet, when confronted at an Executive Council meeting back in February 1923 by the Home Affairs Minister Kevin O’Higgins with evidence of secret meetings of army officers who were IRB members, Mulcahy had simply denied it.

So there now existed in the Army a combustible mix that could end in its own destruction: two opposing secret or not-so-secret societies, each claiming to be the keeper of the republican flame, circling each other.

In March 1924, the tensions burst into the open when the IRAO broke cover.

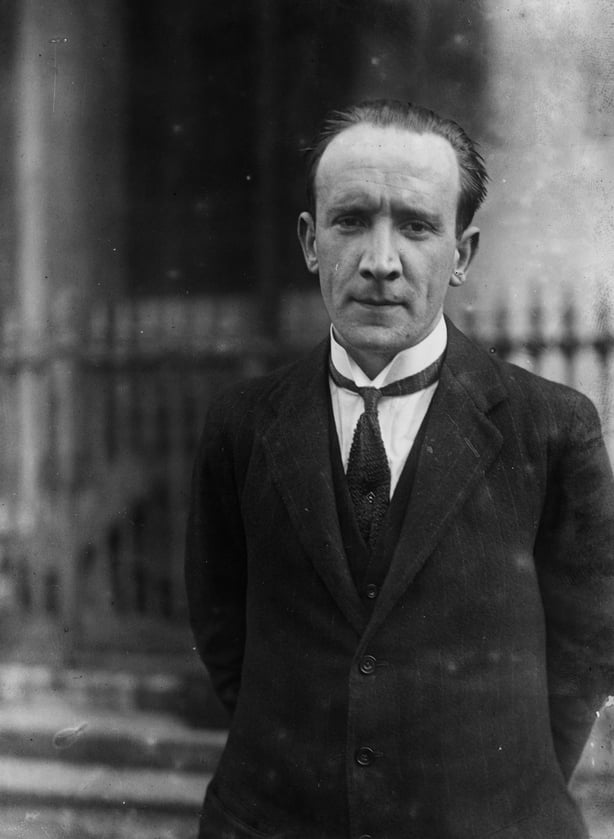

On Thursday 6 March, two officers, Colonel Charlie Dalton and Major-General Liam Tobin, on behalf of the IRAO, signed an ultimatum to the President William T Cosgrave, demanding the removal of the ruling Army Council and a suspension of demobilisation.

The letter claimed the Free State government had abandoned the goal of achieving a republic.

The Executive Council met the next day. Orders were issued for the arrest of the two officers.

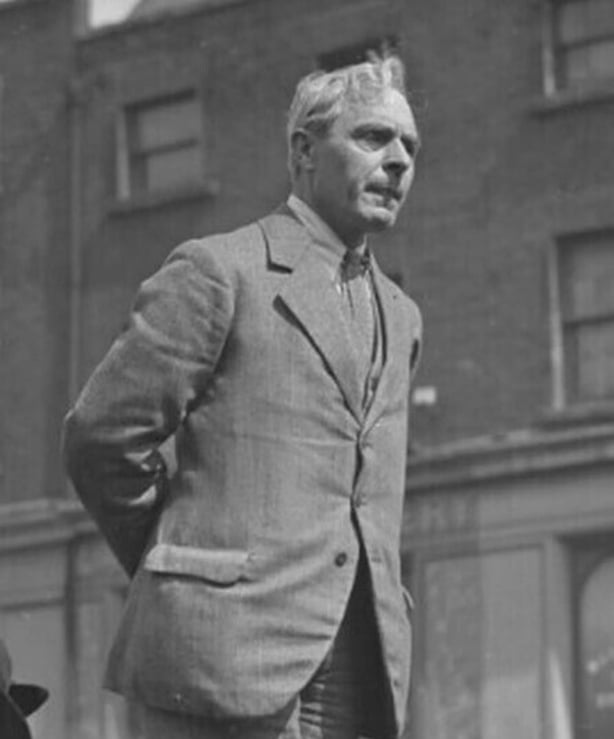

Industry and Commerce Minister Joe McGrath was an open supporter of the mutinous officers and wanted their case heard.

When his home was searched that evening for the two officers, he believed he had been set up by his own colleagues and he resigned from the government.

Mutiny

By Saturday 8 March, it was obvious mutiny was afoot.

Across the country, individual officers were either resigning their commissions or absconding from their posts.

In many cases, the absconders stole arms and ammunition on their way out – machine guns, rifles, pistols, grenades and thousands of rounds of ammunition.

Forty officers resigned and fifty absconded from their posts.

Among the resigned officers were: three majors-general, five colonels, 17 commandants, 12 captains and 12 lieutenants.

This was an officers’ mutiny; no sergeants or enlisted men were involved..

The government wanted a new man at the top in the Army, and on the same day, 8 March, moved General Eoin O’Duffy from his role as Commissioner of the Civic Guard/An Garda Siochána and appointed him as the new General Officer Commanding the Army.

Richard Mulcahy was no longer in command, but crucially, and to O’Duffy’s own frustration, he still did not know the extent of his new powers.

That confusion was now about to be exploited.

On Wednesday 12 March, President Cosgrave told the Dáil that the events of the previous days called for an inquiry into the running of the Army.

This was followed that evening by a second letter to the President from Dalton and Tobin, which was almost a complete climb-down from the first letter, denying there had ever been any intention to challenge the government’s authority.

Smelling a rat

The press and the Opposition in the Dáil smelled a rat.

They believed the pattern of events made no sense:

Two Army officers signed a letter threatening mutiny and demanding the dismissal of the Army Council.

Some 90 officers resigned or went on the run with stolen weapons.

The government’s response was not to announce roundups and arrests of mutineers, but simply that an inquiry would be held into how the Army was run.

Whereupon the two authors of the mutinous ultimatum replied immediately by rowing back on almost all their threats, recognising the primacy of the government’s authority and claiming that their only intent had been to highlight the disorder at the top of the Army.

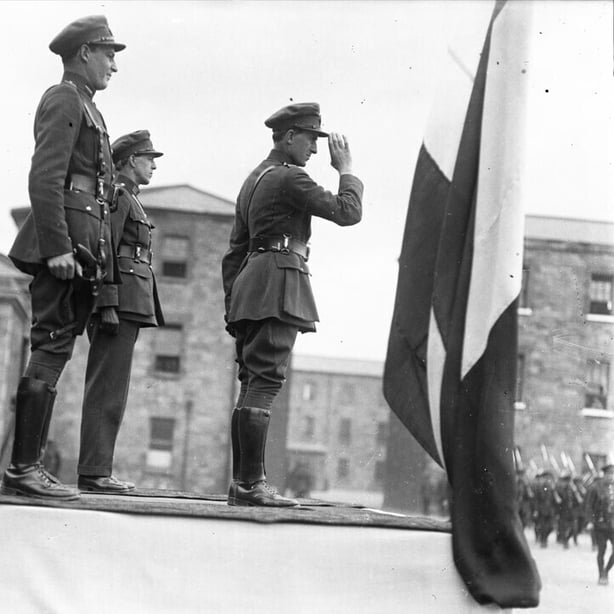

© RTÉ Photographic Archive/Cashman Collection.

The Labour leader Thomas Johnson summed it up: “The government had declared the first letter from the mutineers to be a challenge no government could ignore, a challenge to the democratic foundations of the State, and that arrests had been ordered.”

Then, the mutineers wrote their second letter.

What, asked Johnson, had happened in between the two letters?

“I am afraid that the government has accepted the ultimatum presented to them and has not asserted the authority of democratic government,” he said.

Johnson suspected that key decisions were made on an approach to the mutineers, away from Dáil scrutiny at a closed-door five-hour Cumann na nGaedheal Party meeting the day before.

The Irish Times weighed in the day after the Dáil exchanges:

“Mutiny is mutiny, and …..twenty-four hours cannot change it into a merely frank expression of military discontent, not even 24 hours of treatment in the secret alembic (filter) of Cumann na nGaedheal….in a situation which demanded courage, decision and faith in Irish democracy, the Government has failed to justify the people’s hopes,” the newspaper wrote.

During that Cumann na nGaedheal meeting, Joe McGrath was confirmed as the go-between to meet the mutineers, bringing with him the government’s terms for their surrender.

Mulcahy initially wanted arrests, charges of mutiny levelled at the mutineers and courts-martial. The rest of the Executive Council did not want to go that far.

The terms to be offered were contained in a letter from President Cosgrave to Joe McGrath on 17 March.

The next day General Mulcahy sent a memo to the Army Council detailing the terms put to the mutineers.

The terms:

By 6pm on the 20 March:

– All missing arms and ammunition were to be returned to where they were taken from.

– Those who took the materiel would surrender themselves where they took it from.

– Those who surrendered after giving up the arms and ammunition to be placed under open arrest after giving their parole (their recognition of the government’s authority).

– Those who absconded from their posts to surrender themselves and be put under open arrest after giving their parole.

McGrath later claimed the offer had included re-instatement for most of the mutineers, and that he would not have agreed to be the go-between if this was not on the table. His colleagues denied that that was ever contemplated.

With the terms offered by the government now being considered by the mutineers, and with a deadline for a response set, logic would have dictated that until that deadline of 20 March, nothing would happen.

What did happen next ignited the standoff into a full-blown crisis.

To be continued tomorrow

Read more:

Hunger strike: The last act of the Civil War

Death on a bare mountain: The end of the Civil War

‘It would be a great pity if Collins were killed’