100 years since Army mutiny threatened new Civil War

On Thursday 6 March 1924, the Irish Free State was plunged into yet another crisis when a group of Army officers, angry at being demobilised after the Civil War, threatened mutiny if their demands were not met.

They sent a letter to the President of the Free State, William Cosgrave, demanding that the Army’s ruling body, the Army Council, be dismissed and the process of demobilisation halted.

The letter was signed by two senior veterans of the War of Independence, Army officers Liam Tobin and Charles Dalton.

The government was at the time scaling down the Army from its peak strength of 50,000 at the height of the Civil War, to 17,000, a more realistic number now that the war was over.

The Army was costing the government £10 million a year, almost €900 million in today’s values, an astronomical sum that the new state could not afford to spend indefinitely, given all the other demands for public spending they were faced with.

The allegation made in the officers’ letter was that in the process of demobilisation, veterans of the War of Independence such as themselves were being passed over for promotion or retention in favour of former British Army officers or men who had not seen action in the War of Independence.

They claimed that preference was also being given to officers who were members of the Irish Republican Brotherhood (IRB), the secret society that long predated the IRA.

They set up their own secret society in the Army, the Irish Republican Army Association (IRAA).

They would not accept the government’s position that being a veteran of the War of Independence was no guarantee of a post in the new peacetime Army, that many such veterans would not have the skills required in an Army that wanted to leave its revolutionary origins behind.

Many officers with records of great service to the cause of independence would find themselves out of a job.

Within days, 90 officers had either resigned their commissions (their certification to be officers) or had deserted their posts, stealing arms and ammunition.

The government refuted the allegations of favouritism in choosing officers for retention in the Army, but the mutineers were correct in saying the IRB existed in the force and many officers were indeed members of it, approved by the Army’s Commander in Chief, General Richard Mulcahy.

General Mulcahy was also the Minister for Defence in the Executive Council (the Cabinet).

before Michael Collins’ funeral (Pic: Getty Images)

The government announced an inquiry would be held into the running of the Army and offered the mutineers terms: they would surrender themselves alongside stolen weapons and ammunition, and be placed under open arrest after promising to recognise the authority of the government.

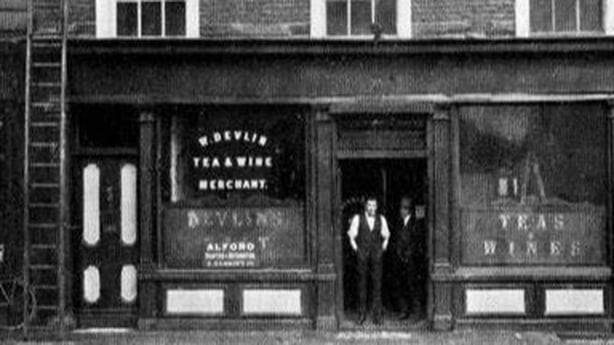

But before those terms could even be considered by the mutineers, the standoff nearly exploded into violence when the Army raided a meeting of armed mutineers in Devlin’s Pub in Dublin, arresting 11of them.

The raid was ordered by General Mulcahy, who did not consult the government before acting.

It happened just as the government was negotiating with the mutineers for their surrender.

So, instead of the government being grateful that the mutineers were in custody, it considered the raid a reckless and dangerous move that could have triggered a gunbattle and started a new civil war.

The resignations of the entire Army Council were demanded – Chief of Staff General Seán MacMahon, Adjutant-General Gearóid O’Sullivan and Quartermaster-General Seán Ó’Murthuile.

General Mulcahy resigned in protest, before he could be dismissed by his colleagues in government.

The generals resigned their positions in the Army as directed.

As a mark of their disgust at how they were being treated, they also resigned their commissions, a move that had not been sought by the government.

The government was so anxious to defuse this crisis that the mutineers, rather than being made to surrender and be arrested and then re-state their loyalty to the state, were allowed simply to resign, after most of the stolen arms and ammunition were returned.

The promised inquiry into the running of the Army was set up in April, and reported in June that the two secret societies, the IRB and the IRAO, were seriously damaging morale and cohesion in the Defence Forces and could not be allowed to continue in existence.

In future, all Army officers being commissioned would have to swear they were not members of any secret society.

The outcome confirmed civilian control of the Army, and is credited with ensuring that, unlike the militaries in other small newly independent countries in the 1920’s and 30’s, there was never the possibility of the Defence Forces staging a coup.

Read more:

Part One: Army mutiny of 1924 threatened to ignite a new civil war